The highs and lows of aid worker salaries

How much you earn as a humanitarian mostly depends on which organisation you work for and where.

Once upon a time, I flew home for the holidays from South Sudan. I had just wrapped up my first three years of humanitarian aid work in the field and my career was beginning to take off. I was feeling good.

Then, at a Christmas party, a childhood friend asked me, “So, are you thinking about getting a job soon? Money must be getting tight after all these years of volunteer work.”

I felt a tingling sensation as the good vibes left my body. I think I managed to mumble, “Mike, you know that humanitarian aid workers are paid, right?”

Although the idea that humanitarians should be unpaid altruists exists and persists, the reality is that the international relief system as we know it would crumble if it were run by volunteers. Managing multi-million dollar aid operations in war zones requires an extraordinary array of technical skills, from procuring and transporting huge amounts of food and medicine across frontlines, to managing refugee camps of tens of thousands of people. Furthermore, humanitarians like everyone else on planet Earth have bills to pay, families to support, and, eventually, retirements to plan for.

So, yes, aid workers earn salaries. The question is, how much?

I get it. You’re busy. You don’t have time to read the whole article but you still want to know how many years in the field it will take to pay off that master’s degree in International Development?

Below is a summary of what you can expect to earn throughout each stage of your career as a humanitarian aid worker, indicated as a monthly salary in USD:

- Entry-level (0 – 2 years): $1,200 – 4,800

- Early career (3 – 5 years): $1,800 – 7,500

- Mid-career (6 – 10 years): $2,700 – 10,000

- Senior-level (11 – 15 years): $4,000 – 13,500

- Late career (16 years +): $5,000 – 17,000

These figures have been cross-checked in numerous (and anonymous) conversations with our network of humanitarians from across the industry who have worked on both the low and high end of the salary scale. After extensive refining, nearly everyone with whom I shared these figures said that they were “pretty accurate”. (This is the level of pinpoint precision that we strive for here at the Insider.)

It should be noted that these amounts are for international humanitarian contracts. National staff salaries vary significantly according to the unique labour market in every single country in the world, and questions about those salary ranges are better answered by someone’s PhD research rather than this website.

Finally, you may have noticed an increasingly yawning gap between the minimum and the maximum salary at each level. For example, at mid-career, who is earning the $2,700 and who is earning the $10,000? In a nutshell, it depends who you work for and where. The absolute minimum salaries are paid by low-budget NGOs in safe countries, while the absolute maximum salaries are paid by the United Nations in high-risk areas.

Let’s get into the details.

Who you work for matters

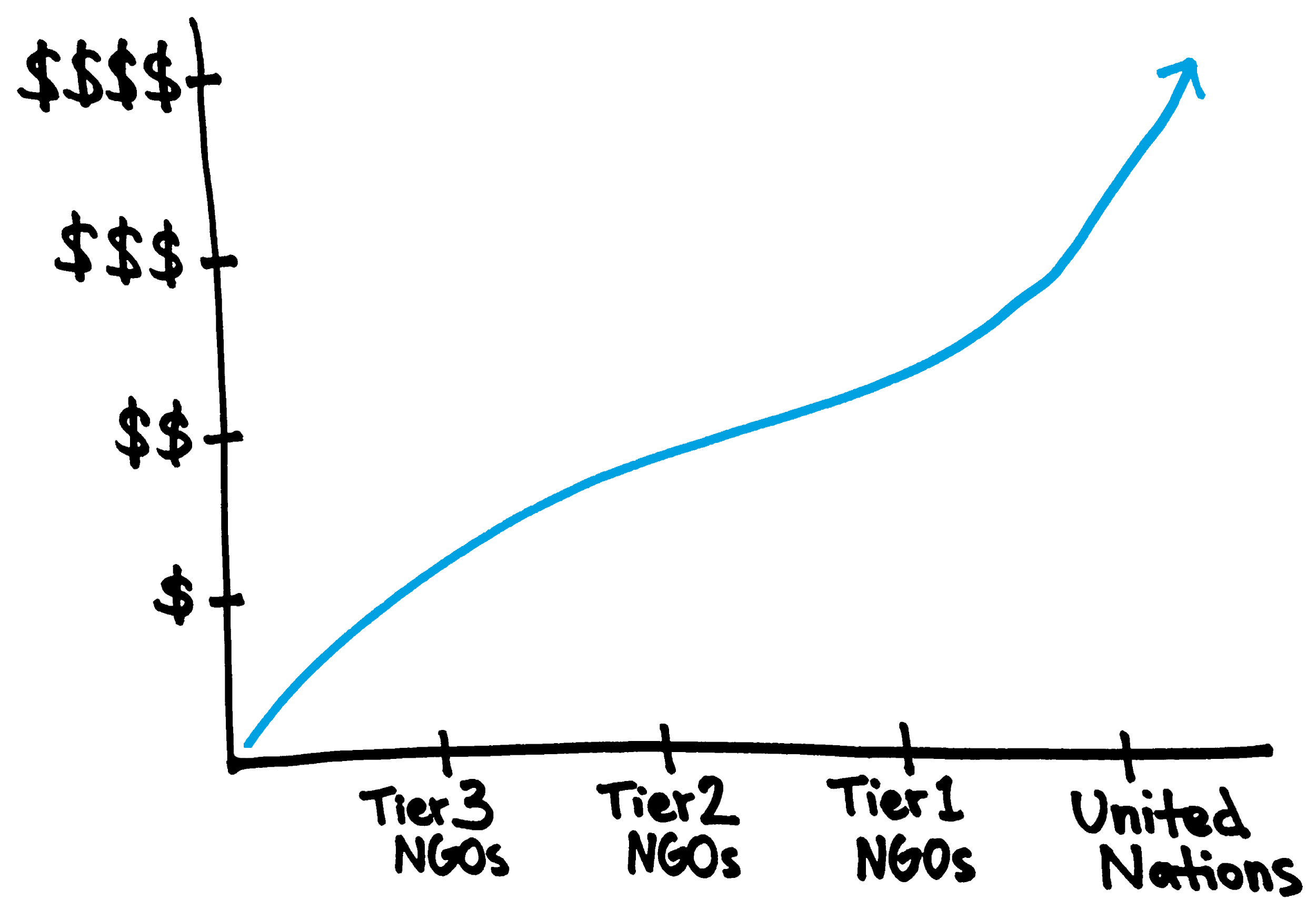

One of the main things that can affect your salary is which organisation you work for.

Imagine two Protection Officers: both posted in Iraq and both with 5 years of experience. One works for the Norwegian Refugee Council and the other with Nonviolent Peaceforce. Despite the fact that both have the same technical skills and may even work physically beside each other in the same duty station, they will receive dramatically different pay slips each month. (Hint: the NRC staffer will earn a lot more.)

Why is this? If most humanitarian agencies – both UN and NGOs – receive their funding from the same small circle of donors, why aren’t salaries standardised across the aid industry? It all comes down to the competitive bidding process for humanitarian funding — which, I’m aware, is not a phrase that usually sparks excitement in anyone with a soul.

But in very simple terms, it is this: When submitting grant proposals to donors, some organisations offer cut-rate bids with low salaries, hoping to win based on cost-efficiency, while other organisations submit bids with higher salaries, aiming to win based on delivering top-quality results. The cumulative effect is a wildly varied array of salary scales across the sector.

So, which organisations pay the highest and the lowest salaries?

- United Nations: When it comes to salaries, the United Nations humanitarian agencies are the Qatar Airways of the aid sector. The compensation is abundantly comfortable, to the point where some claim it’s excessive. Simply put, the UN pays the most.

- Tier 1 NGOs: Scandinavian and American organisations dominate the category of best-paying humanitarian NGOs. A sampling includes: the Norwegian Refugee Council, the Danish Refugee Council, Save the Children, and the International Rescue Committee. In rare cases, their salaries can even surpass the UN.

- Tier 2 NGOs: Filling out the middling section of aid agencies who pay moderate salaries are organisations like CARE, Catholic Relief Services, GOAL, Oxfam, PLAN, and others like them. Many of these British, Irish, and American organisations pay fair salaries. You will have no major complaints with your annual earnings, despite an awareness that there are better-paying options out there.

- Tier 3 NGOs: In terms of remuneration, NGOs like Action Contre la Faim, ACTED, InterSOS, Nonviolent Peaceforce, People in Need, Première Urgence, and Solidarités International are the EasyJets and Ryanairs of the aid industry. Although these organisations are the workhorses of many relief operations, and most are great places to get your first job in the sector, the reality is that their wages are the industry’s rock-bottom.

The goal here is not to shame the low-payers and praise the high-payers, or vice-versa. However, we do believe in salary transparency, especially for aid agencies that receive the vast majority of their financial backing from publicly-funded government grants. Unfortunately, very few humanitarian NGOs share their salary scales publicly. The only one that we are aware of is the Danish Refugee Council, whose international salary scale can by found here.

The United Nations’ salary grid, on the other hand, is available online, although deciphering its byzantine maze of grades, steps, post adjustments, dependant allowances, danger pay, and other calculations deserves a dedicated article on this topic alone.

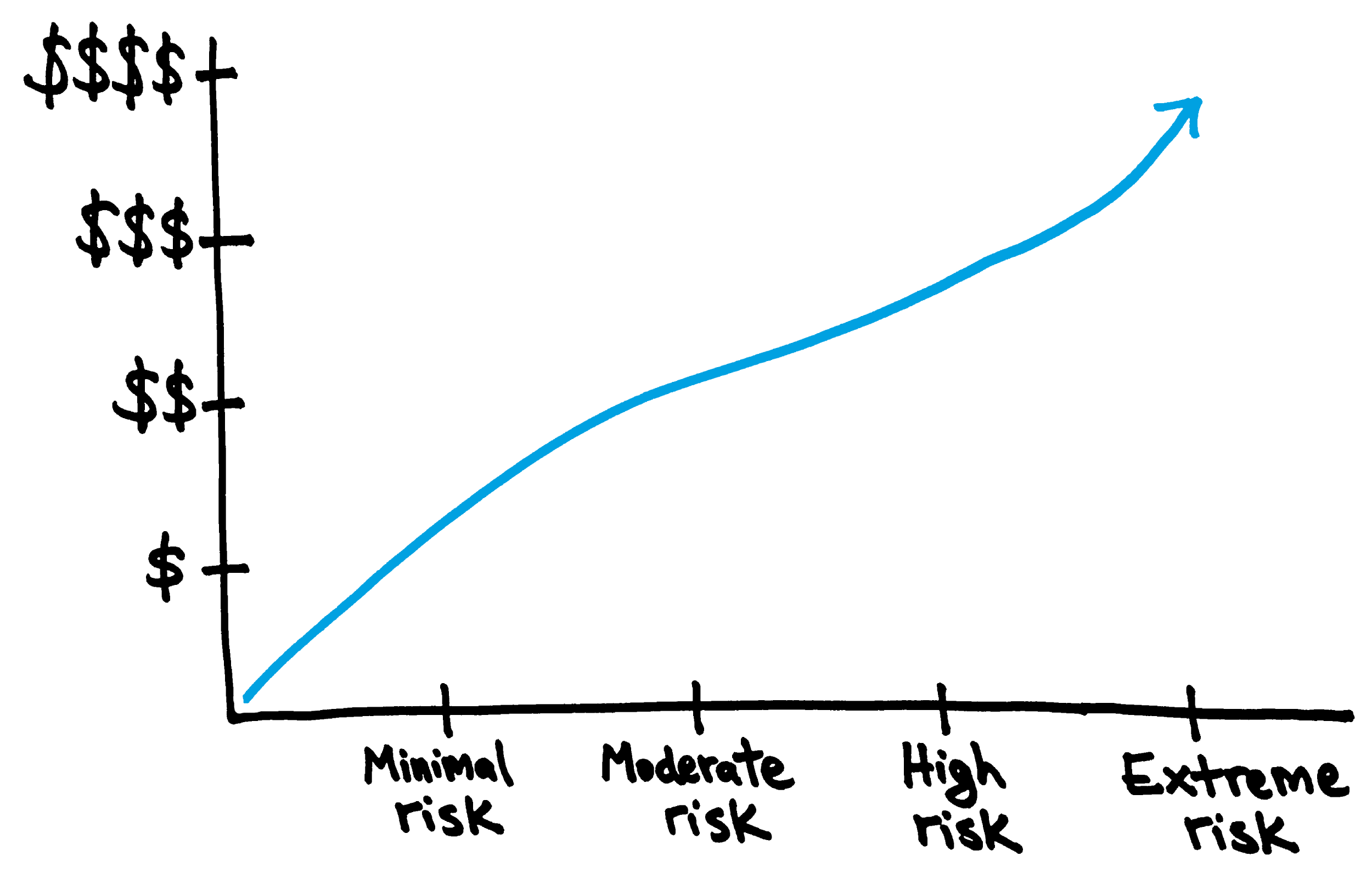

Where you work matters

The second key determinant of your salary is where you are deployed, or in humanitarian lingo, your duty station. There is not much nuance to this one: salaries are generally higher in more dangerous places. This is essentially true for all aid agencies.

The United Nations ranks the level of danger in each duty station across six categories, from Minimal all the way to Extreme. (I’ve always hoped that there exists a secret seventh level dubbed something like Preposterous or Mad, but I’ve yet to find proof of it.) However, this UN Security Level System is actually not linked to staff remuneration. Instead, that is governed by the rulebook of the International Civil Service Commission (ICSC).

Basically, the “field entitlements” that UN staff are, well, entitled to, depending on their duty station, can include: hardship and mobility allowances, a non-family duty station allowance, R&R, and — the classic — danger pay. As you can imagine, the rougher and more remote a place is, the more of these entitlements you’ll qualify for. Each entitlement is added on top of your base salary every month.

On the NGO side, each organisation has its own system for compensating their staff according to the duty station. For the sake of brevity, we can over-generalise and say that most follow a similar formula as the UN: a base salary topped up by increasing amounts of extra money according to the level of risk.

There is an exception to the rule: humanitarian salaries also receive a major boost in some safe duty stations due to high costs of living. Geneva and New York City, for example, the two epicentres of the global humanitarian ecosystem, are distant from wars and disasters, but the aid workers posted there receive some of the highest salaries in the industry.

However, the downside is that because Geneva and New York are the third and fourth most expensive cities in the world, most of that extra money quickly disappears to cover basic necessities like food, rent, childcare, spa days for your dog, and luxury gym memberships.

One more thing...

Before we wrap up, there are a few other salary-related points that you’ll be glad you know.

First, you will not pay income tax on your salary if – big caveat – you work for the UN. In the words of the nameless bureaucrat who writes the UN Office of Human Resources Management’s webpages that look like they’re from 1999: “Most member states have granted United Nations staff exemption from national income taxation on their United Nations emoluments. However, a few member States do tax the emoluments of their nationals. In such cases, the organizations reimburse the income tax to the staff member.” NGO staff, on the other hand, are generally required to pay taxes on their income, either to their home country or to the country in which they are working.

Second, your cost of living will be very low. If you’re posted to the field, your housing and food will often be covered by your employer (especially for NGOs). More importantly, the reality is that there is not much that you can spend your money on in remote or conflict-affected areas. As a result, most humanitarians are able to put nearly all of their monthly pay checks directly into a savings account. A $2,000 payslip is usually $2,000 saved.

Finally, your technical specialisation will not affect your salary. All else being equal, specialists in WASH, Protection, Shelter, NFIs, Cash, Camp Management, M&E, Donor Relations, Finance, HR, or any other expertise will have very similar earning potential throughout their careers. The only exceptions are humanitarian security managers, who are typically ex-military and demand hefty salaries in order to be lured over from the high-paying private security world.

What is a reasonable salary?

In our opinion, a typical, fair, and acceptable humanitarian salary should be somewhere in the middle range of the estimates that we shared at the beginning.

For an entry-level job, if you’re offered close to $1,000 per month, it’s probably too little. If you’re hoping for above $4,000, you might be hoping for a long time. In 2022, we consider $2,000 – 2,500 a realistic salary for an entry-level position. But you can let your childhood friends believe that you’re still a volunteer if you want.

July 2022

Related posts

From medical assistance and food distribution to logistics and finance, your humanitarian career is shaped by your technical specialisation.

Some aid workers spend their career chasing the field. It’s an illusion that is always just over the horizon.

Don’t bother with the United Nations. Aim for NGOs that you’ve never heard of before.

An unlucky number of true anecdotes, success stories, and lucky breaks.

You could skip this article and just go to ReliefWeb.

The veteran Camp Manager explains why the job is among the most challenging in the industry. And why, after nine years, it’s also her favourite.

The Syria-based Protection specialist reflects on the power dynamics of aid and the privileged position that humanitarians often have in fragile countries.

Growing up in rural Sweden, the Red Cross delegate never aimed to be an aid worker. Now, at 33, he has built a career working with communities amid crisis and conflict.