Kathryn

The veteran Camp Manager explains why the job is among the most challenging in the industry. And why, after nine years, it’s also her favourite.

Kathryn is one of the most experienced Camp Coordination and Camp Management specialists currently working in the sector. Since 2012 she has managed dozens of refugee camps and displaced persons sites across Africa, and has coordinated the delivery of humanitarian services in hundreds more. The native Ohioan radiates a sanguine, can-do attitude – essential for camp managers and for anyone born and raised near Cleveland.

These are edited excerpts from our conversation in a Geneva cafe in October 2021.

If you meet someone at a party outside of the aid sector, how do you explain to them what you do for a living?

I say that I work for the United Nations, and then depending on how interested they are I say I’m a humanitarian aid worker, and then if they are still interested I say that I manage camps for displaced people. And then they usually stop listening after that [laughs].

And what do you actually do?

My last position was a Rapid Response Officer for the International Organization for Migration (IOM), specialising in Camp Management. I deployed to new emergencies or emergencies that need staffing support. I was doing it for the past year-and-a-half, and before that I was doing Camp Coordination and Camp Management (CCCM) in a bunch of different countries in Africa.

How long have you been a humanitarian aid worker?

I started in 2012, so nine years. I actually deployed on the day that I graduated from my master’s degree. I missed the graduation ceremony and flew to South Sudan.

Besides South Sudan, which countries have you worked in?

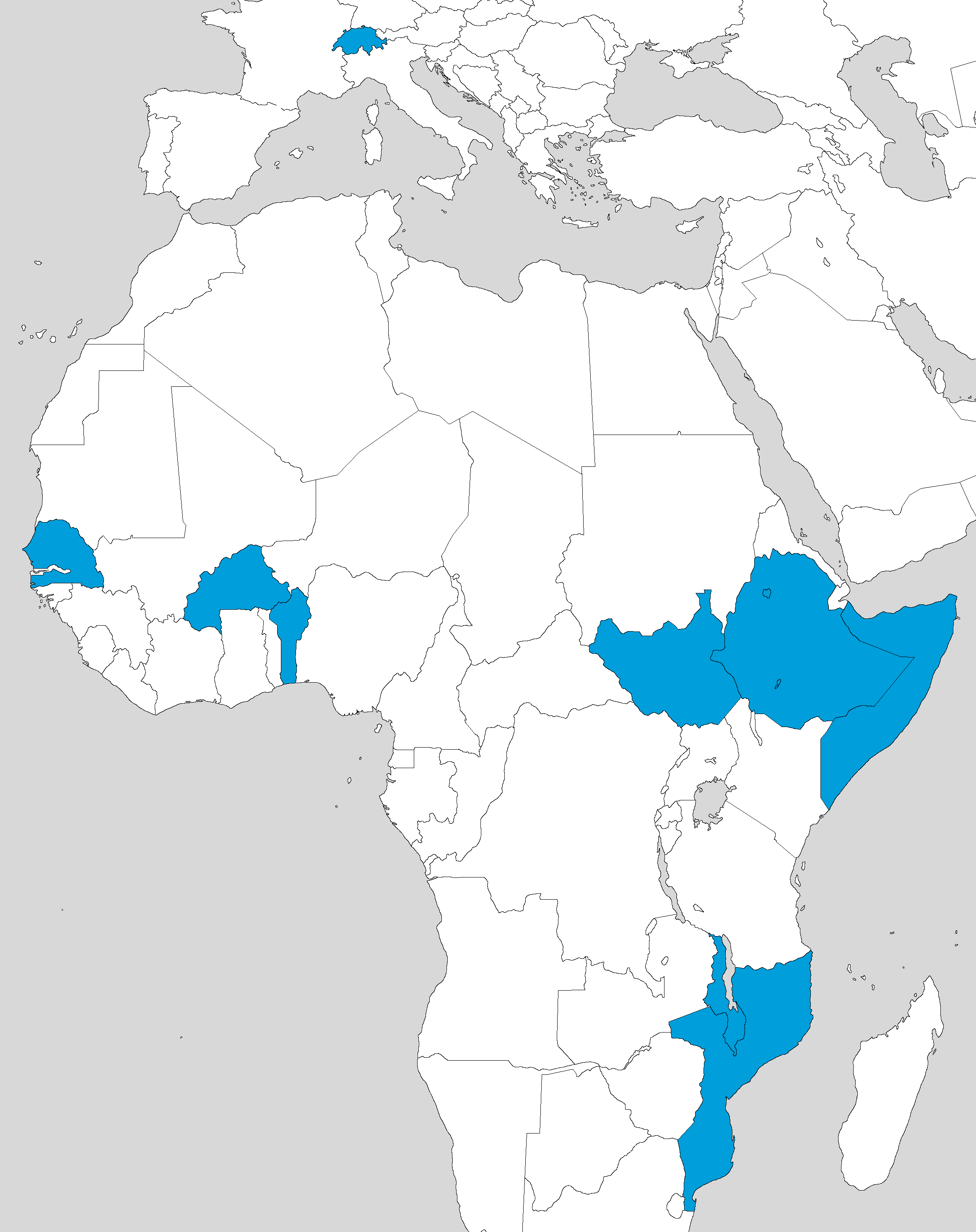

I worked in South Sudan for a long time. I also worked in Somalia, Malawi, Ethiopia, and Mozambique. In West Africa I worked as an intern in Senegal, Burkina Faso, and Benin. Oh, and Switzerland. That’s nine countries! More than I expected actually.

So you’ve only worked in Africa?

[Laughs] I’ve really covered the continent haven’t I? I never worked in the Middle East, only visited. I never worked in Asia either, and have only visited one country there.

Which organisations have you worked for throughout your career?

I started at the World Bank and then INTERSOS, ACTED, a short consultancy with a private company, and then IOM for the last 6 years.

What did you study at university?

I studied Public Relations in undergrad, with a dual major in French. And then International Education for my master’s degree.

Looking back, do you feel like your university studies have played an important part in your career?

The French from my undergrad looks good on my CV. The master’s degree ticks a box on job applications, so I’m glad I got it out of the way. But I don’t think that I’ve used what I learned in my master’s degree in my work.

But my master’s is where I got my first jobs. My teachers helped me a lot with that. If I had not done the master’s degree I would not have gotten any of my first jobs. So it was worth it for the job connections.

When did you decide to become a humanitarian aid worker? Was there a moment?

I will tell you the story! I don’t know if it’s cheesy or not but I will tell it [laughs].

When I was 22 years old I moved to France to be an English teacher. I didn’t want to be a teacher for the rest of my life. I was just doing it to live in Paris for a few years.

My best friend there also happened to be from Ohio. She randomly found this humanitarian organisation on the internet called ACTED, and she got an internship at their Paris headquarters. Soon after, the big earthquake happened in Haiti and she was sent there as a logistics intern. I remember thinking to myself, “That’s so cool. I would love to do that.”

In fact, shortly after I went to this benefit concert in Paris which was raising money for the earthquake relief efforts. I remember being at the concert and thinking to myself, “My friend is actually in Haiti helping people, and I’m just at this concert. I want to be there.” Is that a cheesy story? [Laughs]

Can you tell us how you got your first job of your humanitarian career?

During the second year of my master’s degree, I got a consultancy with the World Bank in Washington, DC. My boss there was super cool and also very honest.

He told me, “If you want to get a real humanitarian job you have to go to the field. You have to leave the World Bank. The World Bank is for grown-ups that have experience, and it’s going to be a waste of your career if you just work here. You’re too young.”

He said, “I’m going to send you to South Sudan for three weeks. We don’t need you to go, but it’s like a gift because you’ve done a good job. While you’re there, get a job with an NGO.”

So I did! I met someone in Juba who did education in emergencies. We had coffee together and she told me that I should apply for her job because she was leaving soon.

So my World Bank boss drove me to my job interview at INTERSOS in Juba! [Laughs] In the end I got the job and started working for INTERSOS. That’s how I got my first job. After a year at INTERSOS I moved into Camp Coordination and Camp Management, and I’ve been doing that ever since.

Is there one job that stands out as your favourite?

My favourite work experience was in 2016 when I was Camp Manager in Wau, South Sudan, with IOM. It was a short-term assignment and I was only there two months. It was a brand new emergency and my job was to set up a new IDP [internally displaced persons] camp.

It was amazing because for several reasons: We had an A-team of experienced people who knew how to do an emergency response. We had infinite money: the donors gave us everything we needed to do things correctly, which is rare. And the IDP community was super nice and easy to work with despite the dire conditions. I would say that was my best work experience.

My favourite job, in general, is being a Camp Manager. One million percent. I love it because it involves daily face-to-face interactions with the community, and it requires being outdoors in the camp every day. After you get promoted beyond Camp Manager there is no more outside work and you basically have to sit in an office forever [laughs].

Being a Camp Manager is the most stressful job I’ve ever had in my life. Camps always have terrible conditions, and you are the one responsible for improving those conditions. When things go wrong, it’s like it’s all your fault even if it’s not. All the expectations and pressure from the displaced community, the humanitarian agencies, and your senior management back in the capital – it’s all focused on you as the Camp Manager.

But it’s also the most rewarding job I’ve ever had, because you can make big differences so fast. And you really get to work together with the community to improve conditions. As a Camp Manager you must have the attitude that you can change things, and that every day the camp will improve. If you just sit back and say “Oh, there’s nothing we can do to fix that,” you’re going to fail. You learn that nothing is impossible, even in extreme conditions.

Basically, Camp Manager is the most dynamic, exhilarating, challenging, and fun job you could ever have. But it’s also incredibly stressful so you can’t do it forever.

Can you explain what you do on a daily basis as a Camp Manager? What does an average day look like for you?

When I was Camp Manager in Juba, I would typically leave the office and head to the camp by 7:30 in the morning. When I arrived at the site, I would either go directly into the camp and meet with my team, or I would go into the UN offices next to the camp to have meetings with the NGO partners who worked in the camp.

If I went straight into the camp, I would meet with my team and we would decide what they would be doing that day. For example, we had an infrastructure team who would work on projects like digging drainage or fixing fences. I would go check on the work and ensure that things were progressing.

We also had community mobilisation teams that would disseminate messages and announcements throughout the camp. I would draft the messages, give them to the team, and they would walk throughout the camp shouting the messages into megaphones. Initially I thought it wouldn’t work but surprisingly people always listened to the megaphones [laughs].

I would also chair weekly meetings with the IDP community leaders. All the NGOs had to come and give updates on the services they were providing in the camp – like health services, or water trucking, or food distribution – and then the camp leaders could give their feedback and raise any issues. We did those kinds of meetings once or twice a week. And they lasted for hours, sometimes up to three hours.

We usually had to leave the camp around 3 – 4pm due to security restrictions and curfew. I would wrap up in the late afternoon, talk to the team, say “great job!”, and decide what we were going to do tomorrow.

Finally, I would get back to our office around 5pm and then I would start on the admin work that had piled up during the day: responding to emails, drafting meeting minutes, sending out important announcements to partners, and that kind of stuff until around 8pm. It’s a long day.

What do you love about camp management?

I love working with people. Every camp management job – no matter what level – means working with a lot of people. You’re coordinating the humanitarian response, you’re working with the displaced people, with the NGOs, with your team. There is a lot of daily interaction with people.

I also like the travelling and the cultural aspect of the work. I think it’s super interesting to get to know the culture and the people of a place, rather than to just doing a quick deployment. I like to learn about what works in what certain places and why.

Looking back, what has been the most memorable moment of your career?

I’ll tell you about one moment from when I was working in Tongping camp in Juba in January 2014. The South Sudan civil war had just started a few weeks before and tens of thousands of people had fled into this UN-protected site. This was my first week working in the camp, and the conditions were just terrible.

Then one night there was a huge rainstorm. It was really bad. The next morning a small team of us woke up very early and went to the camp just after dawn to do an assessment.

Usually camps are noisy places – people are cooking, staying busy, going here, going there – but this morning as we entered the camp it was silent, dead silent. That’s very weird in a camp of tens of thousands of people. It was eerie.

The entire site was flooded. Water was up to our thighs. Everyone in the camp was just quietly trying to pull their soaked belongings out of the water. There were children hanging onto mattresses to stay dry.

I remember thinking that everyone in the camp had already had a terrible thing happen to them only a few weeks before – being displaced by the civil war – and now they had another absolutely terrible thing happen to them. It was a moment I won’t forget.

Not all aspiring aid workers want to go to the field, but many do. What advice would you give to someone who wants to go to the field?

Get a job with an NGO. If you start with the UN you will never learn what you need to learn. NGOs are the ones implementing the projects on the ground, and if you work for an NGO you will learn how to do humanitarian work yourself. But if you go right into the UN, you will only learn from reading reports, not by doing.

If I was a hiring manager and you gave me two candidates to choose from: one who had several years of experience at an NGO in the field and the other who started her career as an intern at the UN and stayed in the UN, I would hire the NGO person.

What is the hardest part about a career in aid work, aside from the day-to-day challenges?

There are so many difficult aspects. The travelling is really hard. If you’re a couple and you’re both humanitarians, or even if only one of you is, it is difficult.

You also lose touch with people back home. As an American I think it’s especially hard because the US is far away from everything and you’re not able to go home as often as others.

Is there something that you wish someone had told you about this career before you started in it?

It is hard to get out of this career once you’re in it. There is a point where many people want to leave humanitarian work and do something else because it is a tiring career. But they find it difficult to get into another line of work.

Another thing is that you should not be wooed into taking any and every job that is offered to you. There are more jobs than there are aid workers. They need us more than we need them. So always consider first where you want to be in your personal life. Taking promotion after promotion in difficult countries is not worth it. It’s better to be in a location where you have a better life – like friends or a partner or safety or the ability to exercise – rather than just trying to get promoted, promoted, promoted. Because there’s not much at the top. Like, do you want to be the most important person at the UN? You know what I mean [laughs]?

Think about where you want your personal life to be, because it can be very hard to have a personal life in this career. Ten years goes quick!

On that note, where do you see yourself in five years? Do you think you will still be working in the field?

Oh, that’s a good question! I’m going on special leave now, and I have nothing planned. I don’t know if I want to do this work anymore or not. I like it a lot but I also want to have a normal life. I would love to have a mix where I could live somewhere nice and also do interesting work.

I’ve done everything that I wanted to do in my career over the past ten years: I got a job at the United Nations; I worked in emergencies; I travelled; I saved enough money. I feel that I’ve run out of goals and now I need to make new goals. I think my new goals will be more personal than career-oriented in the next ten years.

January 2022

Related posts

The Syria-based Protection specialist reflects on the power dynamics of aid and the privileged position that humanitarians often have in fragile countries.

Growing up in rural Sweden, the Red Cross delegate never aimed to be an aid worker. Now, at 33, he has built a career working with communities amid crisis and conflict.

From medical assistance and food distribution to logistics and finance, your humanitarian career is shaped by your technical specialisation.

An unlucky number of true anecdotes, success stories, and lucky breaks.

You could skip this article and just go to ReliefWeb. But why skip all the fun?

Don’t bother with the United Nations. Aim for NGOs that you’ve never heard of before.