Ivan

Growing up in rural Sweden, the Red Cross delegate never aimed to be an aid worker. Now, at 33, he has built a career working with communities amid crisis and conflict.

Ivan is a philosopher humanitarian, equally at ease meeting armed groups in the Chadian deserts as he is authoring dissertations on international law. His career in aid work is remarkable because it almost didn’t happen: he worked in a retirement home, with special needs children, and as a postal carrier in Sweden before finally starting university at age 23.

In the subsequent decade Ivan has earned three degrees (one bachelor and two masters), learned two new languages (French and Arabic), and spent years in the field with the two grand institutions of humanitarian aid (the United Nations and the Red Cross).

Ask Ivan a simple question about how he got his first aid job, and he will soon be expounding in great detail about how to solve the systemic problems of humanitarian assistance. Therefore, these excerpts from our phone conversation in December 2021 have been edited for clarity (and brevity).

How do you explain what you do for work to your friends and family back home?

My go-to answer is “I’m a humanitarian” or I say that I work in conflict settings. Lately, in my work with the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), I explain about working with weapons bearers and the judicial and political aspects of our mandate.

How long have you been an aid worker and what countries have you worked in?

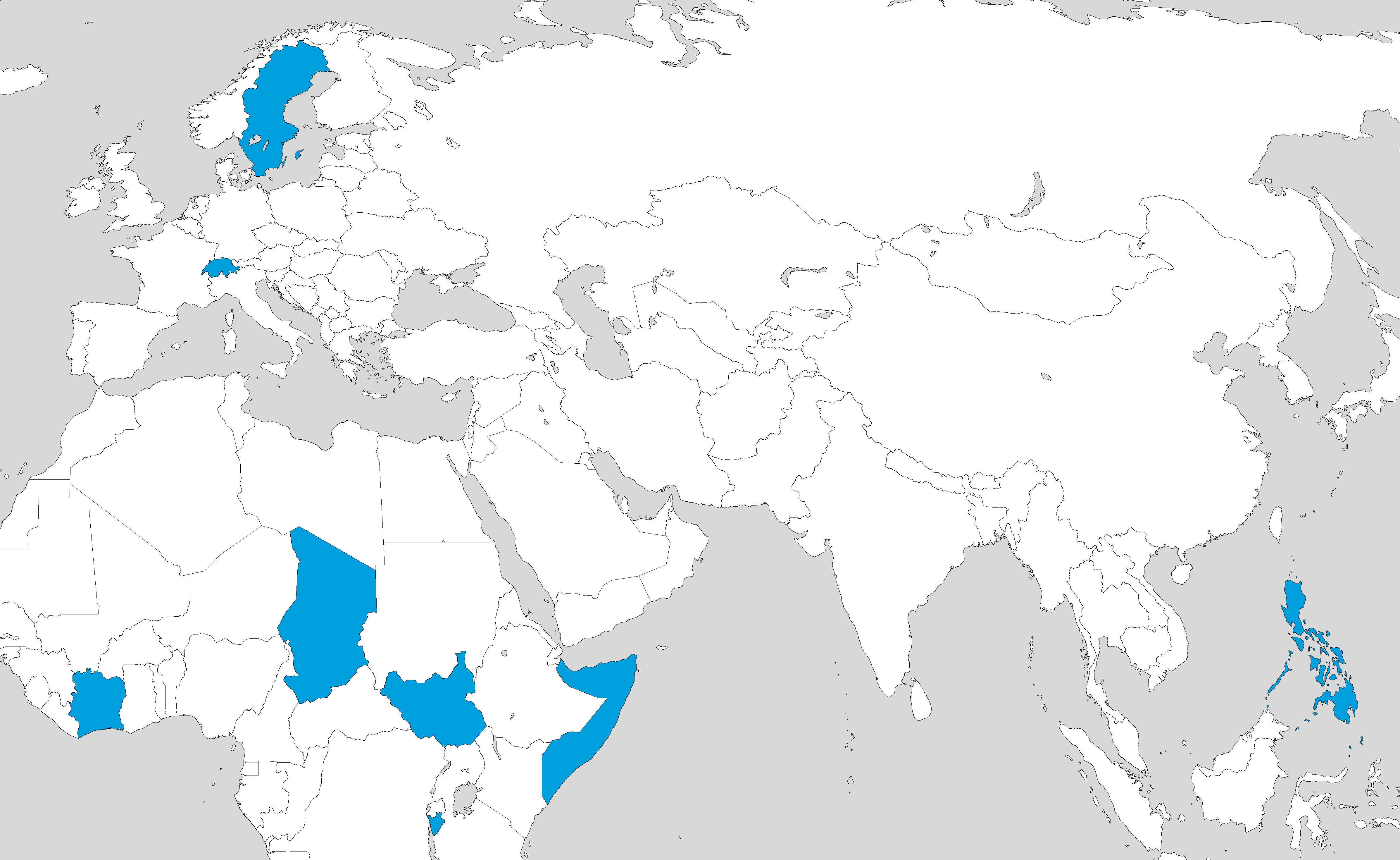

I would say my first humanitarian experience was in 2016, so five and a half years. During that time, I have worked in South Sudan, Somalia, Burundi, Chad, Philippines, Ivory Coast, and in Geneva. Oh, and I’m currently remotely working as a humanitarian here in Sweden.

What did you study at university?

In total, I earned three degrees: a bachelor’s degree in Peace and Conflict Studies from the University of Umeå in Sweden, a master’s degree in International Studies and Diplomacy from the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, and a master’s degree in International Law in Armed Conflict from the Geneva Academy.

However I didn’t start university until quite late – I was 23, I think – and that’s because I come from a very small place in northern Sweden, where nobody really knows what humanitarian work is. The message that I was getting from my community and my family was to get into a practical line of work rather than go to university. But I was very curious and I wanted to study. I felt that politics was interesting, so I began a programme in political science in Umeå, Sweden.

Then one day two women visited from the Peace and Conflict Studies program, they told us about their experiences working in crisis and conflict and the impact it was having on people and communities facing dire situations. This was eye-opening for me. I remember I had this feeling – and I think this may be shared by many people – that If I worked hard I could actually use my privileged position to contribute to improving other people’s lives. Now, ten years later, my perspective has matured somewhat, but that was my point of departure.

Have you used anything from your university studies in your daily work?

My studies have been helpful but not always practically connected to the career that I’ve had. For example, nobody at university told me anything about how to do an NFI [non-food items] distribution in a war-torn country, or even that there was a cluster system for interagency humanitarian coordination! After three years of study, I still didn’t know what OCHA was.

So, if there is anybody reading this who thinks that they need to know everything before they start working, it’s not true. Humanitarian aid is very much an industry where you learn by doing. It’s good to have the theory because it gives you context, but you must learn the practical stuff while working.

Do you think that university programmes in aid and development should focus more on practical humanitarian job skills or more on theory?

That’s a good question. There’s value in both approaches and it depends on your personality. If you’re a student who is thinking: “I know that I want to be operational and I just want to learn how to do direct project implementation in the field,” then I would say that maybe you’re exactly the type of person who would benefit from having more theoretical context. To me it’s absolutely obvious that humanitarian work is never a standalone activity that can be isolated from its socio-political context.

And the other way around. If you’re thinking: “I don’t really care about the nitty gritty details of aid operations on the ground; I just want to help build bridges towards development and peace,” then you’re probably the person who should learn more about the practical, hands-on things. Both approaches should be there in a university program, and maybe this is the problem because usually, as far as I know, they are not.

When did you decide that you wanted to become a humanitarian worker? You were doing something very different with your life until age 23.

I can pinpoint the moment: It was when I was working as an intern with the Swedish Embassy in London, which was my first international job. One day I was sent by my supervisor to a lecture at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London. At the time it was the start of the Arab Spring, and one of the professors was digging into the regional politics in the Middle East. It opened a big discussion about the humanitarian consequences on the ground.

When he was talking, it was almost breath-taking for me. He painted a picture in my mind that there are people suffering and there is a way to do something about it. But, more importantly, he stressed that you should not go in there thinking, “I’m going to save the world.” Rather, his pitch was: “We need dedicated, smart people who have analytical skills and emotional intelligence and who want to use their skills to improve things for other people – other people who are just like you, but who just happen to be in a really rough situation right now.”

Somehow this spoke to me. It’s definitely one of the pivotal moments when I decided that I want to become a humanitarian.

Can you tell me how you got your first job in humanitarian aid? Practically speaking, what did you do to get your foot in the door?

My university in London had a study tour that went to Geneva and visited the United Nations. During the visit someone from IOM came and talked about the organisation, the challenges of migration, and how humanitarian response is linked to political stability and so forth. This really interested me.

And it just so happened – it just so happened – that I had a friend who was already doing an internship with IOM in Geneva. So, of course, I reached out to him and I asked him if there were any openings. He said, “Well, actually, I’m leaving soon…”

So, you know, then I applied and – okay, fine I took his job! Well, it’s not like he gave me his job. He just made me aware of the fact that he was leaving and then I happened to get it [laughs]. I wouldn’t call this nepotism but I think the story highlights the importance of connections, and connections are usually not just given to you, it is something you have to work for and build up over time.

I agree. I think that’s an important point for people to know: probably the best way to get your first job is through networking and knowing someone on the inside of an organisation.

I totally agree.

After that first internship, what other jobs have you had?

After my internship in Geneva, I went to the field as a Shelter and NFI Operations Officer in South Sudan for two years. Then I transitioned into a Cash-Based Interventions Officer position and went on missions to Somalia, Burundi, and the Philippines. Then I became a DDR Consultant – which is Disarmament, Demobilisation, and Reintegration – and went back to Somalia for a year, working with ex-combatants. Those were all with IOM.

The next job I had was with the ICRC as a Protection Delegate and I spent a year in the Lake Chad region. And now I am Head of Desk for West and Central Africa, for the Swedish Red Cross.

Out of all those, which job was your favourite and why?

My first posting in Wau, South Sudan is one of my favourites. I was thrown into it with absolutely no previous field experience. My mission was to re-shelter the living spaces for all 38,000 people living in the camp within three months’ time. And I was supposed to do it using local materials, local traders, and an extreme amount of community involvement. I was given a lot of autonomy and freedom to figure things out. My boss basically said: “Ivan, you’re going to be based out there in Wau and you’ll be in charge of this project. I have a plane to catch. Good luck.”

And it was amazing. It was exactly what I imagined what humanitarian work would be like: I had the technical expertise and the resources from my organisation, and the community had the ideas. So I spent a lot of time working closely with the affected population to enable those grassroots solutions to take place. I think that’s the best role that a humanitarian worker can play: facilitating peoples’ own path to recovery and resilience. And that’s why I liked it so much.

Now I also really like my current job with the Swedish Red Cross, because I’m seeing the other side of the spectrum. I’m not very operational and I do a lot of project administration: budgeting, reporting, and providing technical expertise to our teams on the ground.

I like the job because I’m able to take field experience and use it to support other people who are where I used to be. I know what it’s like to find yourself in the field in the middle of nowhere and you’re supposed to get results and you don’t even know where to start. So, every time one of our field delegates or a member of our project teams comes back to me and says, “I tried out that strategy we discussed and we’re getting good results,” it makes me really proud of the work that I’m doing. I feel that my work is having an impact, even though it’s indirect.

Has there been a most memorable moment of your career?

I do have a most memorable moment, again in South Sudan. It really is a memorable country.

The moment came during that first project in Wau, which I just mentioned before, when I spent three months setting up this local market inside a refugee/IDP camp. The project culminated all on one day when we planned to open the doors to the market and everyone would come running in, get the raw materials for their shelter upgrades, and then the whole transformation of the camp would happen. At least that was the idea.

The market was set to open at 7:30 in the morning. I remember it was just after sunrise and everything was ready. We opened the doors to the market and… There was nobody there. It was just completely empty.

I remember thinking, “All this effort, all this money, all this time, and it’s just going to fall completely flat. This work is just impossible. Don’t ever try to do something this complicated again. Don’t ever try involve the community or strengthen resilience or any of that stuff that you read about. It doesn’t work in real life.”

And while I was having this inner monologue with myself [laughs], I saw on the horizon this South Sudanese woman walking towards me, wearing her traditional outfit. As she came closer, I saw that she had three or four kids running barefoot after her. The morning sunlight hit them from behind and the dust swirled up from their feet as they ran – it’s getting very poetic now! When they reached the market, they looked at me and held up their voucher with a big question mark in their face. I pointed them to the community guy in charge who explained it to them, and they went into the market and picked up their shelter materials.

Then I looked up and suddenly I could see from afar this big crowd walking towards us, all with big smiles on their faces. Within two hours, the entire market was successfully emptied of supplies and people throughout the camp were busy upgrading their shelters.

It was just an amazing thrill. We made it work! It was so memorable because it was the first thing that I did on my own – well not on my own, with the community and my excellent colleagues – as an aid worker.

I think if that would have failed, I might have become a slightly cynical humanitarian. By the way, you should have an article about how to avoid becoming cynical because that is a real issue in the aid industry.

I agree. It’s all too common for aid workers to become jaded. How have you avoided it? And how can someone who is about to start their career avoid it?

Well actually, most of the time, I don’t think the cynicism comes from seeing a lack of results in your field work. I think it mainly comes from psychological pressure and exhaustion. I think that’s the root cause. Nobody gets into humanitarian work thinking, “I don’t believe in humankind” or “I don’t believe in human rights.” Because then you would do something else, naturally. But a lot of positive, big hearts do become cynical because the pressure in this line of work is just overwhelming.

What would you say is the hardest part about a career in humanitarian aid work?

Maintaining a functioning relationship with your partner, your family, and your friends. This is the hardest thing. It’s hard because you are moving around constantly as an aid worker. And when you do get to visit home, you find that you have gained new perspectives on things that your friends and family might not have thought about and it can be hard for others to understand why you do what it is you do. Likewise, they have evolved in ways that you haven’t – it isn’t a competition. Even if you’re lucky enough to have a partner who is understanding, you still have to spend a lot of time away from each other because the chances of you finding a mission in the same place is quite slim.

It’s interesting that you didn’t mention the physical hardships – the rain, the heat, the malaria, the war, the danger. These are the things that people outside our sector assume are the most difficult aspects of aid work.

The psychological hardships are so much worse than the physical ones. We have to be honest: these days people are so freaking good at logistics that I never actually feel worried about my health nor my comfort. Sure, I did have both Covid and malaria at the same time while in Chad [laughs], but I never really feared for my life. There is always a health team in touch with you; there are evacuation plans in place, and your organisation will even fly you out if there is an emergency. You are very well taken care of in terms of health and security.

With all these safety lines, you are constantly reminded about the fact that your life is very different from the people living around you, and it can make you feel awkward, but then again, if you were to go through the same hardships, you wouldn’t be able to do anything to improve the situation would you? And you would certainly not have been sent there in the first place.

Is there something unique about a career in aid work that you love?

I love that I get to work directly with people. As you go to different countries you will experience a lot of different cultures, but you will also realise that there are common denominators, something that we could potentially talk about as a “common humanity.” You begin to see that the fundamental ways of processing emotions, of going through hardship and joy, remain the same. I’m talking about this on an emotional level, then we have cultural interpretations of what to think about and do with these emotions, and this varies greatly. I enjoy this psychosocial, perhaps even anthropological aspect of my work, and I’ve grown as a person through these encounters.

Not every aspiring aid worker wants to be in the field, but I think many do. What advice would you give to someone who wants to go to the field and stay out of the office?

It’s mostly just about getting out there. Because once you have access to the humanitarian world, you will be able to easily jump in different career directions. For example, I started as a Shelter and NFI Officer, which is not something that I was dreaming about. But it was my ticket into the humanitarian sector.

Practically speaking: Apply to internships. Send out tons of emails and CVs. Go onto ReliefWeb, ImpactPool, UN Jobs, etc. Ask for opportunities proactively. Reach out to your network. Don’t have one? Start building it. At the end of the day, getting a job is a numbers game. It’s competitive, but it’s not so competitive that you won’t ever stand a chance. The stars will align, but you have to make sure that when the stars do align, you have already reached out and sent those emails or applied to those jobs.

I want to add something else: When you’re just starting out, don’t forget that if you go and do an internship with a local NGO in your hometown, that will open doors too. For example, when I was a student, I was president of the student wing for Amnesty International in Umeå, and I was also working with the regional working group for the Swedish Red Cross. And those things really count, especially when you start looking for your first international humanitarian position.

What do you wish someone had told you about this career before you started it?

I wish someone had explained to me more about the high turnover. You know, how you go to a place and you stay there for only one or two years before moving on to the next posting. A few years ago, I read an article about humanitarian aid in a country in the Middle East, and the article said that most aid workers don’t even speak one word of Arabic. I remember thinking, “That’s so messed up. If I would ever go to any country, the least I would do is learn the language.”

Now, with my experience, I hear how ridiculous this sounds. It’s just not possible. As an aid worker you’re moving back and forth to different projects all the time, and you acquire a global profile. The expertise that you develop is not location-bound, but rather it’s organisational, or technical, or thematic. I wish someone had told me all of this beforehand.

The last question is looking ahead. Where do you see yourself in five years, in terms of your humanitarian career?

In five years, I would have changed organisations at least once or twice again [laughs]. Ideally I would be in a coordinating position where I’m allowed to develop strategies and be present in the field but not on a permanent basis. I would maybe be a thematic specialist covering a larger area or a region. I would be a kind of spider in the web: pulling different operational responses together, going out and motivating people, meeting communities, and having a very active role but based in headquarters.

In the long-run, I want to be in a place where I can take care of myself, my body, and my well-being. I want to be in a place where I can take care of my relationships: my family and my partner. The field is an extremely important experience. You have to go through it if you want to be a good humanitarian, or at least if you want to work in humanitarian operations. But it takes a toll on you – psychologically, mentally, and physically. You cannot get away from that and you have to accept and adjust sooner or later. Or become a burnt-out person with nothing else but your job to make you feel like your life has any value. And in that case, you might end up doing more harm than good to both your colleagues and the people you serve.

So, no more missions based in the deserts of Chad?

Never say never, but not for now. Insha’allah, one of your readers will pick up on that offer [laughs].

February 2022

RELATED POSTS

The veteran Camp Manager explains why the job is among the most challenging in the industry. And why, after nine years, it’s also her favourite.

The Syria-based Protection specialist reflects on the power dynamics of aid and the privileged position that humanitarians often have in fragile countries.

Take a peek inside aid worker accommodation, from apartments and guesthouses to containers and, yes, tents.

Some aid workers spend their career chasing the field. It’s an illusion that is always just over the horizon.

An unlucky number of true anecdotes, success stories, and lucky breaks.

Don’t bother with the United Nations. Aim for NGOs that you’ve never heard of before.