Career specialisations: A complete(ish) guide

From medical assistance and food distribution to logistics and finance, your humanitarian career is shaped by your technical specialisation.

In any career, specialisation is key. Scriptwriters, cinematographers, costume designers, and actors all work in the film industry. But each is master of a very different craft suited to a different personality type.

The same is true for the humanitarian sector. The emergency response officer who organises a food distribution in the field, the grant writer who designs the food project proposal, the logistician who manages the fleet of food-carrying trucks, and the head of office who secures the blessing of the local armed group to proceed with the distribution – are all aid workers.

Although many humanitarian jobs require cross-cutting skills (a sanitation officer should know how to build a budget as well as a latrine), the specialisation that you choose will have an enormous effect on your career.

Most aid organisations, from the smallest NGO to the largest UN agency, structure themselves along four broad divisions. These can serve as a rough guide to the main career categories:

- Programmes: This is probably what you already think of as aid work: running a clinic, distributing food, digging wells, constructing shelters, managing a camp, and so forth. Apply for jobs in this category if you want to work closely with the people in need, if you don’t mind a little physical discomfort, and if you enjoy a bit of daily chaos or danger.

- Support: This category is linked closely with programmes, but support staff don’t actually implement the activities. Instead, they might design projects and secure funding, write reports, monitor and evaluate activities, or publicise the achievements of their organisation’s work. A diverse group, support roles attract writers, analysts, and creative types. They also offer some of the best entry-level roles to target for your first job.

- Admin and Operations: The least sexy of the bunch, this category is the workhorse of the humanitarian world. They are the procurement wizards, budget-builders, logisticians, recruiters, and security experts who keep each organisation running. In general, these people are knee-deep in bureaucracy and live to follow rules and regulations.

- Management: The forgotten humanitarians are those who steer the ships: the country directors, chiefs of missions, heads of sub-offices, and other senior managers. Typically they are not technical specialists (or their specialist knowledge is now rather outdated). Internally, their role is to inspire staff and make difficult decisions. Externally, they manage the personal relationships with local government officials and other aid organisations. They are usually strategic thinkers and charismatic leaders.

An outline of technical specialisations

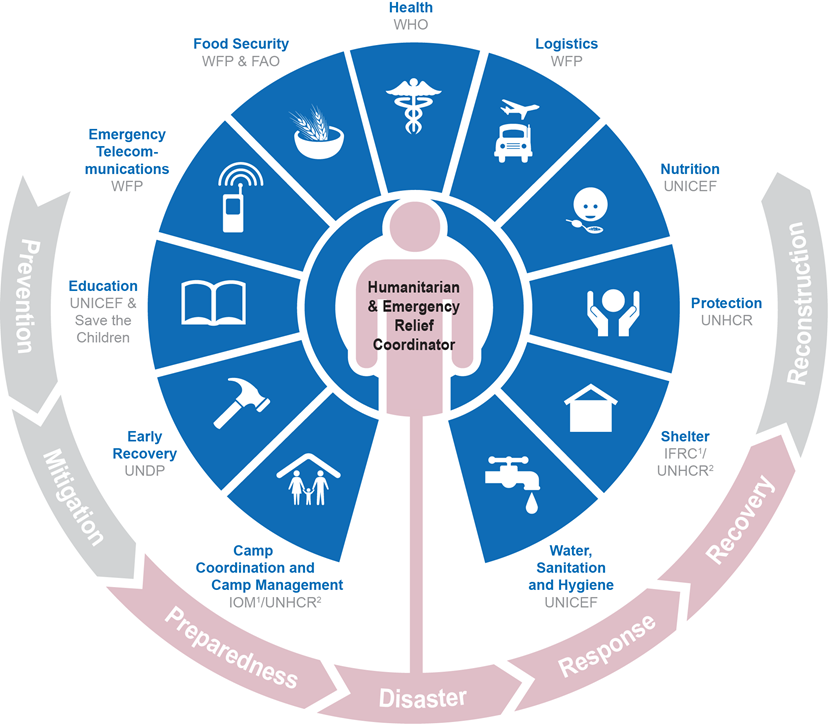

This article will focus only on the first category: Programmes. Within it, the career specialisations are generally broken down according to “cluster”.

“What the #$%& is a cluster?” you may rightfully ask.

Well, you can learn about the Cluster Approach in more detail elsewhere but, in brief, clusters are groups of organisations in each of the main sectors of humanitarian action, and are assigned by the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) with clear responsibilities for humanitarian coordination. In essence, clusters are the building blocks of the international humanitarian response system.

We will focus on the following seven main technical specialisations. These are the ones that you will find active in most humanitarian responses. (You can click each link below to skip to its section.)

- Camp Coordination and Camp Management

- Education in Emergencies

- Food Security

- Health

- Protection

- Shelter and NFI

- Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH)

Camp coordination and camp management

As the name suggests, the work of camp coordination and camp management (or CCCM) takes place inside camps – often ranging in size from a few hundred people to tens of thousands of refugees or internally displaced persons (IDPs).

Uniquely, CCCM actors don’t provide direct assistance in their camps. They don’t distribute tents or administer medical care or build latrines. Rather, their primary responsibility is to coordinate the activities of the other humanitarian agencies and actors, and to ensure that the services provided meet Sphere standards. In addition, camp management also registers newly arrived families, ensures active community participation in the governance of their camp, and even relocates or constructs entirely new camps if necessary.

As the public face of the humanitarian response, much like the mayor of a city, a camp manager’s strongest asset is their personality: their leadership and ability to negotiate, convince, charm, or even coerce others to improve life and living conditions for the camp’s residents. In this way, CCCM has a powerful effect on the quality and perception of humanitarian services for thousands of people.

CCCM job types: There are really only two main roles under CCCM: Camp Manager (managing a single large camp) and CCCM Cluster Coordinator (coordinating multiple sites in an area). There are other support roles such as Camp Officers or Community Mobilisation Officers, but these are often junior positions in the ladder leading up to Camp Manager or Cluster Coordinator. The downside to this narrow field is that there are not many CCCM jobs available at any given time; the upside? It’s a small pool of people globally, many of whom know each other and refer jobs.

Organisations that specialise in CCCM: There are two UN agencies who lead CCCM globally: the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). IOM generally leads on sites for internally displaced persons sites, while UNHCR’s mandate is for refugee camps. Beyond the lead UN agencies, there are really only two NGOs that specialise in CCCM: ACTED and the Danish Refugee Council. If camp management interests you, focus on these two organisations. With ACTED you will have a better chance to get your foot in the door. DRC usually hires candidates with more experience.

You might like CCCM work if: You like working with lots of people on a daily basis, and you like being outside. In CCCM, you spend most of your days in the camps talking to people: meeting in tents with community members, coordinating with the NGO and UN personnel who are providing services, and liaising with military or security forces. It varies from setting to setting, but most camp managers will be in their camp for several hours every day. It can be hot and sweaty work. In general, CCCM is ideal for humanitarians with high social skills and keen emotional intelligence, rather than analytical, hide-behind-the laptop personality types.

Education in emergencies

The above photo of a ragged school tent is an apt symbol for education in emergencies. The sector is chronically the most under-funded in nearly every humanitarian context, with only around 3% of global humanitarian funding allocated to education. The effects are readily visible on the ground: emergency schools are often understaffed, housed in unsuitable structures, and lack sufficient basic learning resources like books and writing materials.

When lives are at stake, it’s hard to argue against prioritising water, food, shelter, and medical care. But when when crises become protracted over months and years, the children affected by them can miss crucial educational development and stunt their future lives and careers. Education in emergencies therefore is crucial to building a foundation for recovery in any community that has been displaced by war or natural disaster.

Education in emergencies job types: Interestingly, teaching jobs are not among the roles for international education staff. The barriers of language (and payroll) mean that teachers are usually recruited locally. International staff typically serve in regional or country-level Project Manager or Advisor roles. They might be responsible for everything from teacher recruitment to construction of schoolhouses, from designing curricula to procuring and distributing a semester’s worth of school supplies.

Organisations that specialise in education in emergencies: The Education Cluster is the only cluster co-led by a UN agency and an NGO: United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and Save the Children.

Funding is often so meagre that grants for education in emergency activities are frequently won by very small and/or very local NGOs in the field. A few of the big-name organisations (like NRC or Save) do implement education activities, but in general the spectrum of organisations is wide and varies dramatically according to country and continent. Sort ReliefWeb job openings by “Education” to see some examples.

You might like education in emergencies work if: You have a passion for education or for children. Education in emergencies is one of perhaps only two humanitarian sectors – the other being health – that is well-suited for a direct transition from a domestic career to an international humanitarian career. If you have experience as a teacher or school administrator, you may already have much of the requisite technical knowledge and skills in order to become an Education Officer or Project Manager in a humanitarian context.

More information about education in emergencies:

Food security

Fighting famine and delivering food to people in need is perhaps the quintessential humanitarian action. In an emergency context, food security activities ensure that food is available and accessible in areas affected by disaster, and that people do not starve.

The classic image of humanitarian food aid usually involves sacks of essential food items being distributed off the backs of trucks to malnourished people. This scenario can be the reality sometimes, but food security work also addresses larger topics such as markets (are local markets functioning so that people can buy their own food?), livestock and fisheries (are animal populations healthy after a shock event?), agriculture (have crop planting cycles been disrupted by human displacements?), nutrition (is the food that people are able to access of adequate nutritional value?), and others.

Food security job types: Its mission may be straightforward, but food security work involves a diverse range of technical jobs. There are field officers who plan and organise food distributions, as well as nutritionists, economists, farmers, veterinarians, animal husbandry experts – not to mention the huge array of operational support roles that do the silent work of logistics and procurement, keeping the global food aid supply chain moving by land, sea, and air. For a sampling of food security jobs, go on ReliefWeb filter by “Food and Nutrition” and browse.

Organisations that specialise in food security: There are two main UN agencies specialising in food security: the Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) and the World Food Programme (WFP). The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) is also involved in nutrition for children.

But for an entry-level position, you will have more success applying to one of the innumerable NGOs that actually implement the activities of these UN agencies on the ground. There are scores of NGOs that do food security work, and there are no clear specialist organisations for this category. Even those whose organisational names reference food are not necessarily “better” or more specialised than other big international NGOs at food security.

You might like food security work if: You are a more technical, left-brained type of person. Feeding millions of people worldwide, or even just thousands of people in one community, generates huge amounts of data and requires enormous logistical capacity. The majority of the jobs, although not all, are on this analytical and logistical back-end, rather than on the front-facing community side.

More information about food security:

Health

The origins of organised international humanitarian aid can be traced to medical relief work on the battlefields of the 19th century. Today this tradition is kept alive (no pun intended) in the global Health Cluster and the array of organisations that provide medical aid.

But nowadays humanitarian health work is much more comprehensive and includes running clinics in remote areas, vaccination campaigns (even before Covid), combating specific diseases like Ebola or HIV/AIDS or measles, mental health care, surgery and trauma care (whether on the battlefield or in the maternity ward), emergency first aid, building the capacity of local health care systems, and more.

Health job types: Contrary to what you might think, the sector is not only for doctors and nurses. Many medical NGOs divide their recruitment pages between medical and non-medical roles. A sampling of medical positions includes anaesthesiologists, surgeons, nurses, dentists, midwives, paediatricians, and mental health officers. Non-medical positions, on the other hand, are mostly coordination roles: the people who manage and support the teams of medical professionals.

Organisations that specialise in health: Among the UN agencies, the World Health Organisation (WHO) serves as the leading authority on global issues. However, in the field, WHO doesn’t directly implement many activities; instead it is UNICEF and IOM that have large and active health programs on the ground. The UN Population Fund (UNFPA) is also a player, focusing on sexual and reproductive health.

The lion’s share of humanitarian medical work is actually done by NGOs. Médecins sans Frontières (MSF) – known in English as Doctors Without Borders – is the gold standard of medical non-profit organisations and needs no introduction. Its breakaway sister, Médecins du Monde and the International Medical Corps (IMC), are two other top-tier NGOs that focus on emergency medical assistance and health care.

You might like health work if: You are already working in the health field, naturally. There is perhaps no smoother transition into aid work than that from domestic doctor or nurse to humanitarian doctor or nurse. But even if you don’t have the credentials to wear a stethoscope, joining a medical NGO or UN agency can be extremely rewarding because the results of your work are immediately visible: ailing people are cured, babies are born, and death can be met with dignity. These direct and tangible impacts of your work are rare even in other sectors of aid work. Building a latrine or handing out a bag of food – no matter how needed – can rarely compare to the deep human emotions connected with saving a life or easing someone’s pain.

More information about health:

Protection

Protection work has nothing to do with armed security escorts or bullet-proof glass. Rather, the word refers to protecting the well-being of vulnerable people who’ve been caught up in conflict or other emergencies.

Protection can be viewed as a parallel to the social work sectors found in many countries, except it exists in contexts where those systems have collapsed. Indeed, the work involves responsibilities that are similar to traditional social work: case management, domestic and sexual violence issues, support for disabled persons, and ensuring access to basic services (in our case, humanitarian services). It often includes one-on-one consultations and addressing situations that are confidential and deeply personal. For example, while someone working in shelter/NFI or food security may be concerned with distributing items to 5,000 families, a protection specialist will be focused on solving a domestic violence case for a single family.

Within the protection sector there are five categories that, together, aim to form a panoply of protection for vulnerable persons in humanitarian settings: general protection; child protection; gender-based violence; land, housing, and property; and mine action.

Protection job types: Protection workers will typically specialise in one of the five categories listed above, although it is not uncommon for people to move between (general) protection, child protection, and gender-based violence during their careers.

Mine action and land, housing, and property are outliers that require different skill sets. Mine action programmes are mostly staffed by ex-military who have experience and training in explosives (their ranks are uniquely dominated by Irish and South African men). Housing, land, and property professionals, on the other hand, typically tend to be human rights experts and people with legal training.

Organisations that specialise in protection: The mandates of both UNHCR and ICRC, each enshrined in international law, involve the general protection of displaced persons and the lives and dignity of victims of armed conflict. Therefore it’s no surprise that these two organisations are titans in the pantheon of protection work.

Down the slopes of Mount Olympus, each of the additional categories has its own lead agency: UNICEF for child protection, UNFPA for gender-based violence, the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) for land, housing, and property, and the United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS) for – you guessed it – mine action. At the field level, there is a smallish pool of specialist NGOs who directly implement protection activities: Nonviolent Peaceforce (NP), Handicap International (HI), Terre des Hommes (TdH), the International Rescue Committee (IRC), and the already-mentioned Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), to name a few.

You might like protection work if: You are empathetic and want to make a difference at the individual level, as opposed to being involved in large-scale operations. If the idea of social work interests you, but you prefer to work abroad rather than at home, protection could be a good fit. For ex-military personnel, mine action provides one of the few non-security pathways into aid work.

More information about protection:

Shelter and NFI

When people flee their homes, they often do so with few belongings. Shelter and NFI specialists aim to address these needs. Shelters are usually an emergency tent or temporary structure large enough for a family. Non-Food Items (NFIs), as the name suggests, can encompass any assistance that is not edible or medical: plastic tarps, mattresses, soap, toothbrushes, forks, diapers, laundry detergent, blankets, shovels, cooking pots… a list of potential NFIs can test the infinite limits of Excel spreadsheets.

Shelter/NFI work can be divided between the procurement and subsequent distribution of items. Procurement is the unsexy back-end. Indeed, choosing, testing, ordering, and warehousing tens of thousands of miscellaneous items can be tedious work. However, it is critically important. If emergency shelters or NFI kits are of poor quality, insufficient quantity, or stored incorrectly, the humanitarian impacts are real.

Distribution, on the other hand, is the front-facing work involving affected populations. Before distributions, beneficiaries must be selected according to vulnerability criteria and registered in a database to prevent duplication of assistance before the items can be physically distributed to them in a secure and accessible location.

Shelter and NFI job types: Despite the wide range of activities that fall under shelter and NFI activities – from checking the quality of spoons to constructing hundreds of bamboo shelters – the spectrum of job titles in the sector is surprisingly narrow.

The largest job family is the shelter and NFI “Officer/Project Manager/Coordinator”, a generalist whose title changes as she moves up in seniority but whose responsibilities and expertise remain broad. Otherwise, there are a few specialists in the sector, including engineers or architects who design shelters, or supply chain specialists.

Organisations that specialise in shelter and NFI: Globally, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) is the convener of the Shelter Cluster in natural disasters while UNHCR leads in conflict situations. Additionally, IOM is often a lead or co-lead at the country level.

For most humanitarian NGOs, procuring and distributing items – even at large scale in a disaster zone – is a piece of cake (although not actual cake because that would be a food item, now wouldn’t it?). The result is that nearly every aid organisation does shelter and NFI programming somewhere in the world. While this makes it difficult to narrow your search, the benefit is that you can probably transition internally to shelter and NFI work from within whatever organisation you happen to get your first job with.

You might like shelter and NFI work if: You have a split personality. If you are a logical thinker whose pulse quickens at the sight of Excel sheets, item lists, price comparisons, technical specifications, shipment schedules, and warehouse stock reports, you will love the procurement side of the work.

On the other hand, if you are a “people person” who gets excited at the thought of going door-to-door registering needy households for assistance, meeting with community members to discuss which shelter solutions would be most appropriate, or spending a week managing crowds (and expectations) while distributing items to thousands of beneficiaries, the distribution side of the work will fit snugly with your personality. Unfortunately the two are inseparable in most job roles. If you only fancy one half, you’ll have to learn to love the other.

More information about shelter and NFI:

Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH)

The water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) sector deals with the dirty side of life, namely excrement and trash, and how to keep people healthy in spite of it. When thousands of people are suddenly forced to live in a crowded camp-like conditions, disease can spread rapidly without access to clean water or proper sanitation and hygiene facilities.

WASH interventions aim to reduce the risk of transmission of a number of diseases including cholera, Ebola, hepatitis in its various forms, typhoid, acute watery diarrhoea, and dysentery. (Health sector actors, on the other hand, would be responsible for treating people who have contracted these diseases.)

The most common WASH activities deployed in the field include supplying water, distributing soap, collecting garbage, and constructing latrines, showers, hand washing stations, and drainage canals.

WASH job types: There is not much diversity to be found among WASH jobs. The words used in the titles may change – Officer, Advisor, Specialist, Project Manager, Coordinator – but each typically has the same comprehensive WASH duties, with either more or less decision-making ability depending on the level of seniority. In general, there are no separate roles for water specialists or sanitation officers or hygiene advisors.

The main variations in the work come from the changing context: your WASH interventions will look different in a camp setting vs. a non-camp setting, or in the arid Middle East vs. equatorial Africa.

Organisations that specialise in WASH: On the UN side, UNICEF and IOM are the most active agencies in the sector, with UNICEF leading the WASH Cluster globally.

However, as in the shelter and NFI sector, there are no standout specialist WASH NGOs, because there are simply so many organisations implementing activities. If you’re interested in the work described in this section, head over to ReliefWeb and sort by “Water Sanitation Hygiene”. The results will give you a sampling of which organisations to apply to.

You might like WASH work if: You are passionate about public health, engineering, community engagement, or all three. Under the public health umbrella of preventing disease spread, WASH splits between construction work (latrines, showers, drainage canals, wells, water tanks, spigots) and community engagement work (changing behaviours and attitudes around waste disposal and hygiene).

In one day you might organise a soap distribution to 2,000 families, supervise the drilling of a new borehole, sort out a problem with the contractor providing water trucking services, strategise how to combat an outbreak of cholera in a camp, check the chlorine levels in your water tanks, and design a multi-lingual flyer to encourage hand-washing. (Actually that would be a very busy day, and I haven’t even factored in lunch.)

More information about WASH:

February 2022

Related posts

An unlucky number of true anecdotes, success stories, and lucky breaks.

How much you earn as a humanitarian mostly depends on which organisation you work for and where.

Some aid workers spend their career chasing the field. It’s an illusion that is always just over the horizon.

Growing up in rural Sweden, the Red Cross delegate never aimed to be an aid worker. Now, at 33, he has built a career working with communities amid crisis and conflict.

The Syria-based Protection specialist reflects on the power dynamics of aid and the privileged position that humanitarians often have in fragile countries.

Don’t bother with the United Nations. Aim for NGOs that you’ve never heard of before.

Take a peek inside aid worker accommodation, from apartments and guesthouses to containers and, yes, tents.

Hiring managers from across the aid industry give their advice on what makes a great CV and cover letter. However, they don’t always agree.

You could skip this article and just go to ReliefWeb. But why skip all the fun?