Aliya

The Syria-based Protection specialist reflects on the power dynamics of aid and the privileged position that humanitarians often have in fragile countries.

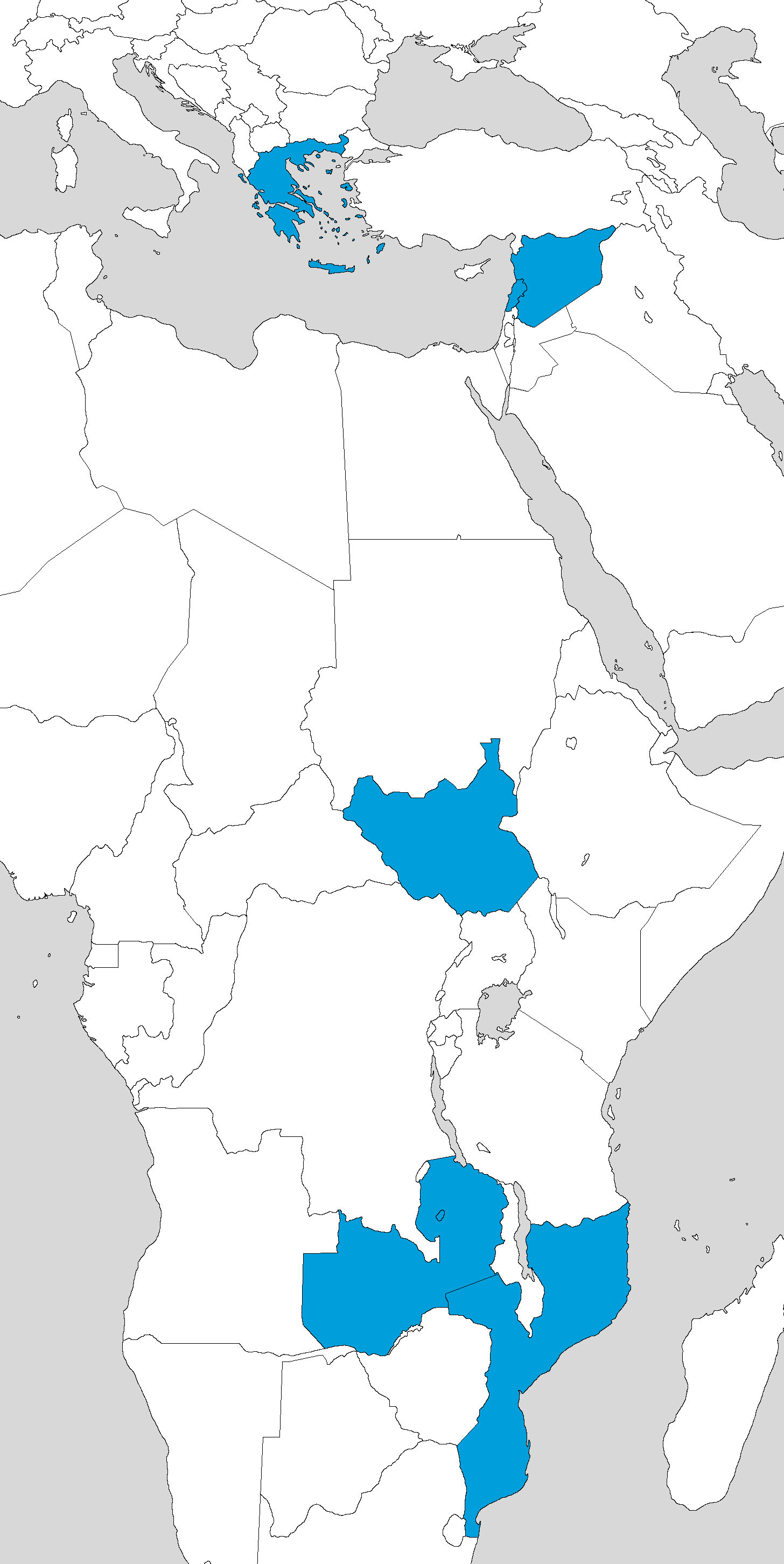

After working for six organisations in six countries in as many years, Aliya has seen the humanitarian sector from many angles. She has often eschewed more cushy job opportunities in order to stay in the field and close to the work. Through it all she has remained lighthearted, reflective, and a rare idealist: a principled, straight-and-narrow-path humanitarian. Aliya’s career has also been peculiarly geographically straight-and-narrow: entirely contained between the 20th and 40th longitudinal meridians, an accidental commitment to humanitarian action within +02:00 Greenwich Mean Time.

These are edited excerpts from our phone conversation in December 2021.

How long have you been a humanitarian aid worker?

I would say that I’ve been doing humanitarian work in some capacity since 2015, so about six years now. I work in humanitarian emergency settings, so my work is focused around things like Protection and specifically Child Protection, which are parallels to the social work sectors in many countries, except I’m working in contexts where those systems have collapsed. Currently currently I am working as a Protection Specialist in northeast Syria.

Speaking of Syria, which countries have you worked in during your career?

I worked in Lebanon, Greece – all over Greece actually – and then South Sudan. I did brief deployments to Zambia and Mozambique. And of course where I am now in Syria.

Which organisations have you worked for?

Relief and Reconciliation for Syria, a small American NGO called LEAP, Lighthouse Relief, Save the Children, Terres des Hommes, and PLAN International.

That’s six organisations in six countries in six years. Why have you moved so often?

I think everyone has their different reasons, but for me I was going with the locations that I was passionate about, with the work that I wanted to do, and with whichever organisation enabled me to do that. Sometimes that required changing organisations.

So it has been about finding the right type of job and the right organisational culture, rather than a better salary or job security?

Definitely, those are the driving factors for me. Hopefully salary hasn’t played into my decision-making too much, but I also couldn’t work for nothing for long periods of time. It definitely has not been about climbing up role-wise or responsibility-wise. I haven’t looked too much at the “level” of the job, as long as I felt I could learn something new or have a good experience in the role.

What did you study in university?

My B.A. was in Linguistics, although I didn’t study a particular language. Then I went on to do a master’s degree, again in language together with English literature. So it was very much the science of linguistics, the science of communication. Currently I am on a second master’s degree in Refugee Protection and Forced Migration. I’m doing that at the University of London, through distance learning.

Your first two degrees are focused on linguistics, while your third degree is directly tailored to aid work. Do you feel that what you chose to study has had an effect on your humanitarian career?

That’s a very thoughtful question. My linguistics studies have had an impact on my worldview and how I interpret things around me. They helped me to open up to different cultures and to know about intercultural communication.

I had no clear intentions about my career when I was studying my undergraduate and first postgraduate. I was leaning toward teaching English as a second language. I knew by that stage that I did not want to stay in the UK. But I did not have a clear calling to humanitarian action or to aid work.

How did you get your first job in the humanitarian sector? What was the story behind it?

Early on, I did an internship in Geneva with a very small NGO. The guy who ran the NGO was very motivated to give his advice to us. I remember one of the things he said to us interns was: “Go out and do something.”

So I did go out and volunteer, and that played a big part in getting my first job. In my case I was in Lebanon teaching in Palestinian camps as a volunteer. Eventually I was offered a job with someone who was starting his own NGO in the north of Lebanon to respond to the Syrian refugees arriving there. That connection was mainly due to just being present in Lebanon already as a volunteer and building a network.

So do you agree with what your boss in Geneva said: that aspiring aid workers should just get out there and do something to jumpstart their career?

Yes, but I think I am a bit cautious to advise others to just go anywhere and do anything. I think it’s a bit more nuanced than that. What I would say is: Do something that makes sense to you. Don’t go somewhere just for the sake of being there because you think you might land a job. It has to fit with the issues and locations that you’re passionate about, so that you can do something productive whilst you’re there. For me, wanting to learn about Palestinians in Lebanon was the basis. And then once the Syrian war started, I became passionate about responding to what was happening in that moment in time.

Following your first job in Lebanon, what other types of humanitarian jobs have you had?

After Lebanon, I came to Greece and did front-line emergency response. “Front line response” can mean different things in different humanitarian contexts. On Lesvos it meant being on shore while boats of refugees were arriving, distributing food items, helping people carry their belongings, and sharing information with refugees. Later I led a small team which did night-time boat spotting, and I coordinated with search and rescue teams on the water. I would never have expected to do work like that in my career.

After Lesvos, I worked on the mainland of Greece where I had the opportunity to do Education in Emergencies. I did that for over a year, and then I switched to Child Protection. Later in South Sudan I was able to do both Child Protection and Education in Emergencies.

And now in Syria you are still doing Protection?

Yes. Child Protection was my avenue into Protection more broadly. Protection mainstreaming in health is what I do now.

Throughout your career you have moved around different technical specialisations. Has it been easy to do that?

Yes, I think it is possible to change specialisations, within reason of course. In some technical areas you definitely need the academic background, the training, or the qualifications. I am very aware of the risk of having non-qualified people in technical positions, which unfortunately does happen in our sector.

That’s me. That’s the story of my career.

[Laughs] No, no. I don’t think so. But you know what I mean: there are some jobs where you need a qualification, especially when it comes to working with children.

Which job has been your favourite and why?

That’s too hard! If I look back, working in the north of Lebanon with the very small start-up NGO was not my favourite thing at the time. There were definitely days when it wasn’t the best time of my life. But later on I came to appreciate how much I could do in that job without the bureaucracy of a larger organisation weighing down the work.

But on the other hand I miss – really genuinely miss – my project in South Sudan. We were working with children that were extremely vulnerable, and we were actually able to offer them some protection and support. We did work that was really impactful. We could be proud of our work. To me that is the big difference – and it’s not always a given in every humanitarian job.

Has there been a moment in your career which has been the most memorable?

I always think of the people that we worked with in Lebanon. My NGO was working with one particular community that had moved together from their village in Syria to Lebanon. We were doing community-based education, basically building an informal school for their kids.

In the evenings we would visit the community members in their homes and chat. One evening we were sitting with the community leader, and he was explaining the social fabric of their community, and what things were truly important. For him it was so crucial to do something for the youth. He would say, “We need to eliminate ignorance, because knowledge is power. This is why the education system is so important.” And so on.

Hearing him talk about his priorities for his community – which were so completely beyond the scope of our very technical project – was a very eye-opening and humbling moment.

Up until that point I feel like I was unaware of the traditional power dynamics that exist between an NGO and the community that they work with. But this conversation really shifted my perspective. It opened my eyes to this power dynamic, and to the fact that this power dynamic is based on the fact that an NGO has aid funding.

In humanitarian work, sometimes you only see people in terms of how to implement your project. You only talk to them about your project. But the reality is that you are just a very small part of the life of a person or a community. We were narrowly focused on building the school, printing the textbooks, and ensuring that the teachers were paid, while he was looking at the bigger picture. It made such an impression on me because it put me in my place. I was a bit naïve initially, and this conversation was part of my learning. That’s why it has stayed with me.

Can you explain what you do on a daily basis? From the moment you wake up on an average day, what does that day look like?

My current job in northeast Syria is doing Protection mainstreaming in health, so a lot of my work is organising trainings on Protection-related issues, such as Child Protection, Gender-Based Violence, and Persons with Disabilities inclusion. I develop guidance, create standard operating procedures, and do trainings for the field teams.

For example, if there is an assessment planned, then me and my colleagues ask questions like: Do we need to do this survey or does the data already exist? Where are we implementing it? Who are we asking these questions to? Then I create the assessment and train the team on how to conduct the survey in the field. All that training needs to be planned and coordinated, so a lot of my job is the nitty-gritty details of when and where and how are we going to do various trainings.

Even though I’m based inside Syria, a lot of the work that I’m doing is from my office, and a lot of it is remote. Some of that is due to Covid restrictions, but also there isn’t a need for an international staff to go out into the field every day. We have a team of national staff who speak the language and are in a better position to deliver the activities. One of my main reasons for going on field visits is to listen and learn from the staff about the needs and challenges, and how to improve the programming.

I spend about 40 to 50 percent of my time in the field traveling to different locations in northeast Syria, visiting with the teams and delivering trainings, usually at health facilities in IDP camps or in non-camp settings.

But in the last few years I have noticed that as you become more of a technical specialist, you become less field-based and spend more time in the office, even if that office is in the field.

What do you love about your work?

I really love the traveling. Well, actually I enjoy moving to a country and staying there for a while. That’s my version of travel [laughs]. I also enjoy working with different people from different backgrounds. I think that’s something I really like about aid work: being able to build your own knowledge of certain places in the world, based on your own experiences of living and working there.

What is the most difficult part about a career in aid work?

Maybe it’s a cliché, but I definitely think that personal relationships are hard. You have to be aware of that going in.

A second thing I would mention is mental health. In recent years it has become less taboo, but humanitarian aid is still a sector that suffers from this toxic culture of: “If you’re not working 200 percent then you’re not hardcore. If you’re not completely exhausted, then you’re not doing it right.” Admitting that it’s okay to look after your well-being is something that the aid sector needs to get better at.

There is something else too, which I mentioned before: There are certain power dynamics about being with an international organisation and having funding in a country that is very fragile. A lot of my personal struggle has been figuring out how to become aware of and address my own unconscious biases. As international staff, it’s important to be aware of the position of privilege that you have. Sometimes I’ve been very disappointed in the way that aid workers and aid agencies conduct themselves in this regard, and I ‘ve questioned whether my own actions are respectful and in line with social values I want to embody. That is another challenge that I’ve been confronted with.

Those power dynamics have often created a strange mix of guilt for me. Because I’m working for a large humanitarian organisation with funding, and because I’m an international staff with different living conditions, I’m immediately on one side of those power dynamics. You can’t change it. You have to deal with it and it’s always uncomfortable.

It is. And I believe that you have to acknowledge that discomfort as part and parcel of the work.

What advice would you give to a future aid worker who wants to get into the field?

I’ve personally loved my own journey so I would repeat it. I would say: work in an area that you’re passionate about in a voluntary capacity and let it grow from there.

What I’ve also come across other people doing is seeking out an internship with an organisation at home that can open up doors internationally. But I think if you do that, then you have to directly express that you have a desire to move to an international position. Hustle a little bit for yourself. Be vocal and direct about what your intentions and hopes are.

I would add to that: Have a second language. Although I’m a little hesitant to say that because I know so many successful aid workers who don’t have a second language.

What do you wish someone had told you about this career before you started in it?

I wish someone had said to me: You can actually make a vocation out of humanitarian work. If you’re interested in engineering, you can make that a humanitarian job. If you’re interested in IT, or research, or law, you can make those humanitarian jobs. I wish that I had more of a qualification or skill in a particular technical background. That’s what I would tell my younger self. But I don’t know it’s going to help anyone else [laughs].

I agree. If you love photography or social work or dentistry, and you also want to do aid work, you can combine them. You don’t need to separate them. I think the fact that so many aid workers – myself included – studied development or aid creates a situation where you have a lot generalists leading technical projects, which is not ideal.

Exactly.

Last question. You’ve been working in the field for six years. You’re in Syria now. Where do you see yourself five years in the future?

I’m 33 now and if you’d spoken to my 20-something-year-old self you would have gotten a totally different answer [laughs]. I know that the next five years will be a period of change for me. Whilst I’m really happy and enjoying the field work right now, I don’t want to be doing it still in five years. Part of my current studies is about shifting gears. I’m looking at advocacy roles and human rights research jobs at smaller organisations at home in the UK. These are points of interest that I can transition into later.

I think what you’re describing is very common in our sector. There is often a transition into and then out of field work, usually around one’s mid-thirties. There are also people who never transition out, and that has its own consequences: missing out on relationships, family, and normal life. Do you have any thoughts on that?

I would say “think about it” rather than “don’t think about it” [laughs]. I think once you start doing field work it’s very easy to postpone those bigger questions. Without you knowing it, years pass.

I agree. This isn’t my interview, but the advice that I would give to aspiring aid workers is, in one sentence: If you want to do field work, do the crazy stuff as early as you can. Because you never know what will happen. You might fall in love and then want to be together with that person. Or your parents might get sick and you need to move home. Or you might become sick. Anything can happen and the field work can end at any moment. So if you want to do crazy adventurous things, do it as early as you can.

I agree. Use that time to your advantage and try not to worry too much about long-term goals if what you’re doing in the moment is something you enjoy and are learning from.

January 2022

Related posts

Growing up in rural Sweden, the Red Cross delegate never aimed to be an aid worker. Now, at 33, he has built a career working with communities amid crisis and conflict.

The veteran Camp Manager explains why the job is among the most challenging in the industry. And why, after nine years, it’s also her favourite.

Budgets and audits may not seem likely pathways to an impactful humanitarian career. But for the seasoned Finance Manager, the job is about people, not numbers.

Some aid workers spend their career chasing the field. It’s an illusion that is always just over the horizon.

Take a peek inside aid worker accommodation, from apartments and guesthouses to containers and, yes, tents.

You could skip this article and just go to ReliefWeb. But why skip all the fun?