The hierarchy of humanitarian job titles

Every profession has its pecking order. When I worked in the film industry many years ago, I knew that the Director was the boss of the set. But what about the 1st Assistant Director? The Unit Production Manager and the Production Coordinator? The Key Grip and — everyone’s favourite job title — the Best Boy Grip? As a young Production Assistant, it was less clear to me how everyone else fit into the hierarchy, except that I was at the bottom.

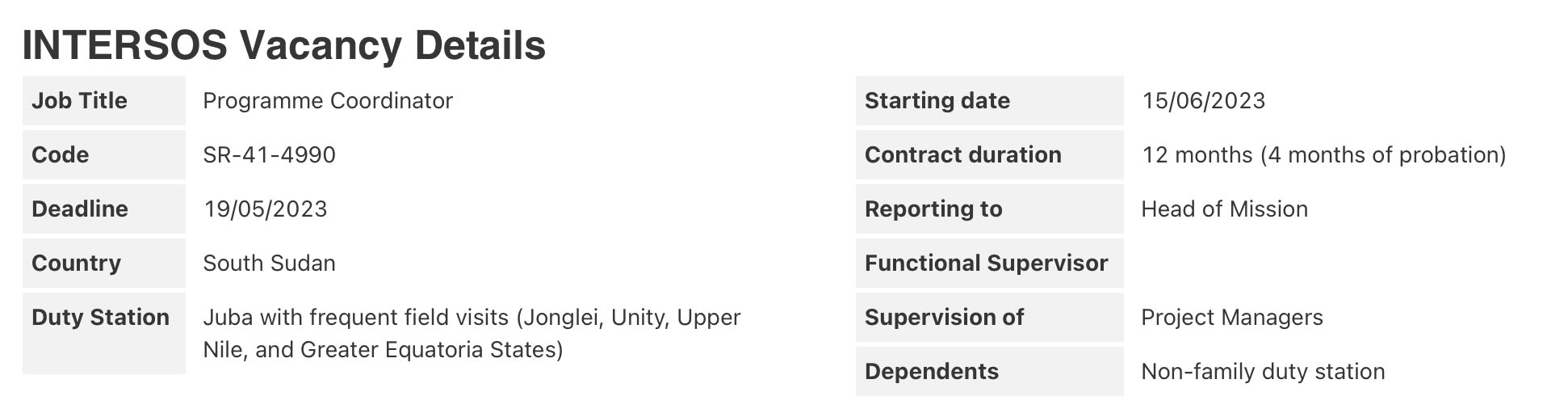

Similarly, you may have already wondered to yourself while scrolling through humanitarian job advertisements: What is the difference, anyways, between a Project Officer, a Project Manager, and a Programme Coordinator? What about a Senior Project Assistant and a Junior Project Officer?

As an aspiring aid worker, understanding the industry’s job titles is not only useful in charting a future career path; it’s also crucial to ensure that you’re targeting the appropriate jobs in your applications right now.

In this article, we will not cover the different technical career specialisations in the aid industry (you can read all about them in another article), even though they are a part of every job title. Rather, we will focus on the hierarchical terms in the titles: the coded words that tell you who’s the boss of who in every humanitarian crew. Yes, we could have just labelled this article, “Humanitarian organigrams explained”, but be honest — would you have clicked that link?

Caution: Lots of generalisation ahead. Please keep this in mind when sending us your hate mail.

Job title definitions

Before we get to the organisational charts — and I know you’re salivating at the thought — it’s important to define our terms. Below, we have identified the eight most common job titles that you will find in a typical humanitarian country office, whether UN or NGO. We’ve done our best to define them in a way that is easily understandable to young aid workers and that is less migraine-inducing than most job descriptions.

They are listed below in ascending order, from lowest seniority to highest:

Intern:

Interns are the lowest rung on the staff ladder and are often paid only a small stipend, if anything at all. Most humanitarian field internships are actually desk jobs, focusing on reporting, grant writing, or communications. The main skill that these positions require is the ability to write well in English (or French in certain countries). Rarely are they expected to have any technical humanitarian knowledge.

Many international NGOs refer to their field-based internships as “Volunteers” for legal reasons, and so the titles can be interchangeable. (UN agencies, however, will only ever use the term Intern, and UN Volunteers is a separate organisation entirely.)

Assistant:

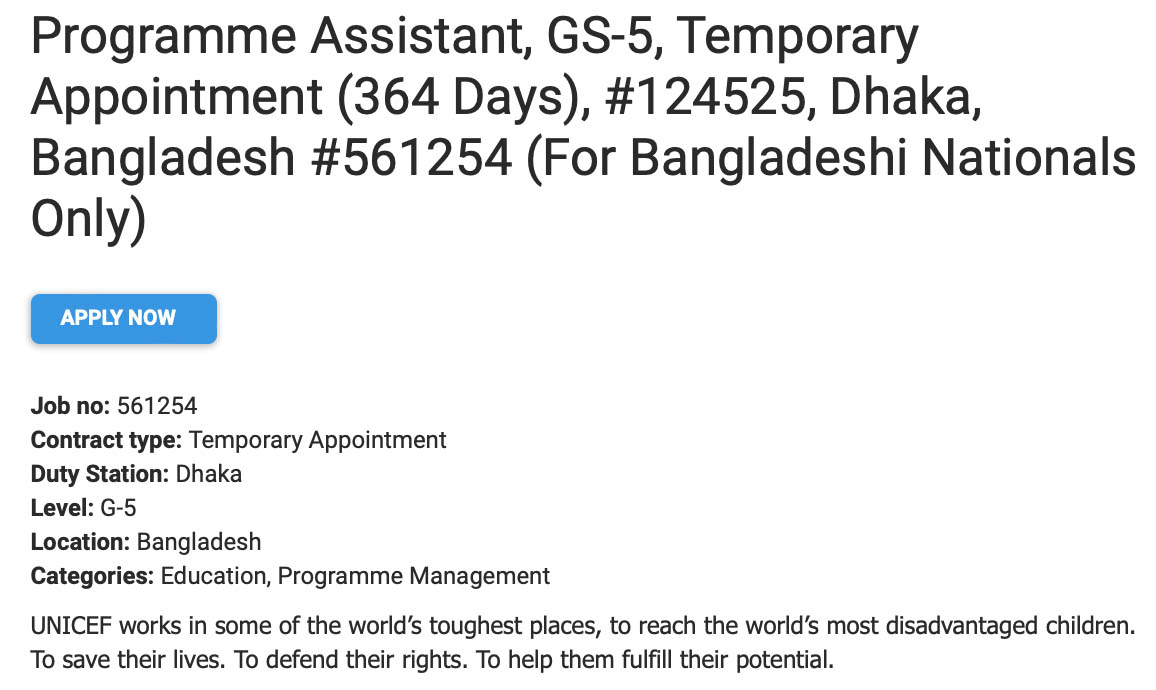

These entry-level field positions are often, but not always, restricted to national or local contracts. This means that somewhere, squirreled away within the job description, you will find a sentence like, “This is a national position and only [country] citizens will be considered.” For UN agencies, national-staff positions are classed under the General Service category, commonly known as G-staff (not to be confused with G-Unit). For example, if the job is posted for Ukraine, then you must be Ukrainian. If you’re not, then your application will be rejected. In the cases when international candidates are allowed to apply, fluency in the local language may be mandatory.

Assistant positions are fantastic entry-points to aid organisations. They are also some of the most interesting jobs because they are the ones often doing the front-line humanitarian response work: distributing relief items, conducting rapid needs assessments, and, in general, working outside in the sun, rain, or cold directly with the people in need. Unfortunately, they are also usually the lowest-paid positions in the sector.

Keep in mind that, because they target the domestic labour market, Assistant positions are often posted on country-specific job boards — for example, like Bayt.com in the Middle East — rather than the big international humanitarian sites like ReliefWeb.

“Senior Assistant” denotes a similar position but with more, well, seniority. These posts may require a minimum of 6 – 7 years of experience and may include managerial responsibilities, such as supervising field teams of Assistants.

Officer:

Unlike in the military or the police, an Officer in the aid sector does not carry a firearm nor extraordinary amounts of authority. In fact, they are typically just one or two steps above Interns. These early-career international positions often require between one year of experience with certain NGOs to two-to-five years of experience in P2 positions with the United Nations.

In general, Officers might supervise national staff but not other international staff, and it is rare for them to have signature authority on budgets. However, Officer-level positions can be some of the most memorable and rewarding international humanitarian roles. Why? Because they are frequently in the field — alongside the Assistants — working directly with the affected populations. Once you start moving up in seniority beyond Officer, time in the field diminishes and time in front of a laptop increases.

The prefixes “Junior”, “Associate”, or “Senior” can be attached to “Officer” to expand the job title’s versatility further.

Manager:

Project Managers and Programme Managers are the corporals of the humanitarian sector. They lead small- to medium-sized teams, usually organised around a technical area, like Protection, WASH, Shelter, Food Security, CCCM, and so forth.

Managers must have some humanitarian expertise as well as the skills to manage projects, budgets, and people. Depending on the context, it could be a team of two and a budget of $100,000 or it could be a team of 50 people and a budget of $10 million. The ability to lead a variety of personalities is essential, as Managers may supervise everyone from junior expat interns to highly experienced national staff and even global specialists who know more about CCCM or Food Security or WASH than they do.

Managers’ contact with the field — even where their own projects are being implemented — is more limited. Instead, they must devote significant chunks of time to office-bound duties: meeting donors, writing reports and project proposals, building budgets, hiring (or firing) staff, and participating in lots of meetings. Field visits to see projects and staff is often a special occasion, rather than a daily routine.

Confusingly, you may also stumble across the title “Area Manager”. These are in a different vein from Project Managers or Programme Managers. Rather, Area Managers are geographically-anchored leadership roles responsible for the full gamut of an organisation’s operations — finance, HR, logistics, procurement, security, and humanitarian programming — within a region of the country. If a Country Director is analogous to a president, then the Area Mangers are like provincial governors. Depending on the organisation, an Area Manager is also sometimes called “Head of Base” or “Head of Sub-Office”.

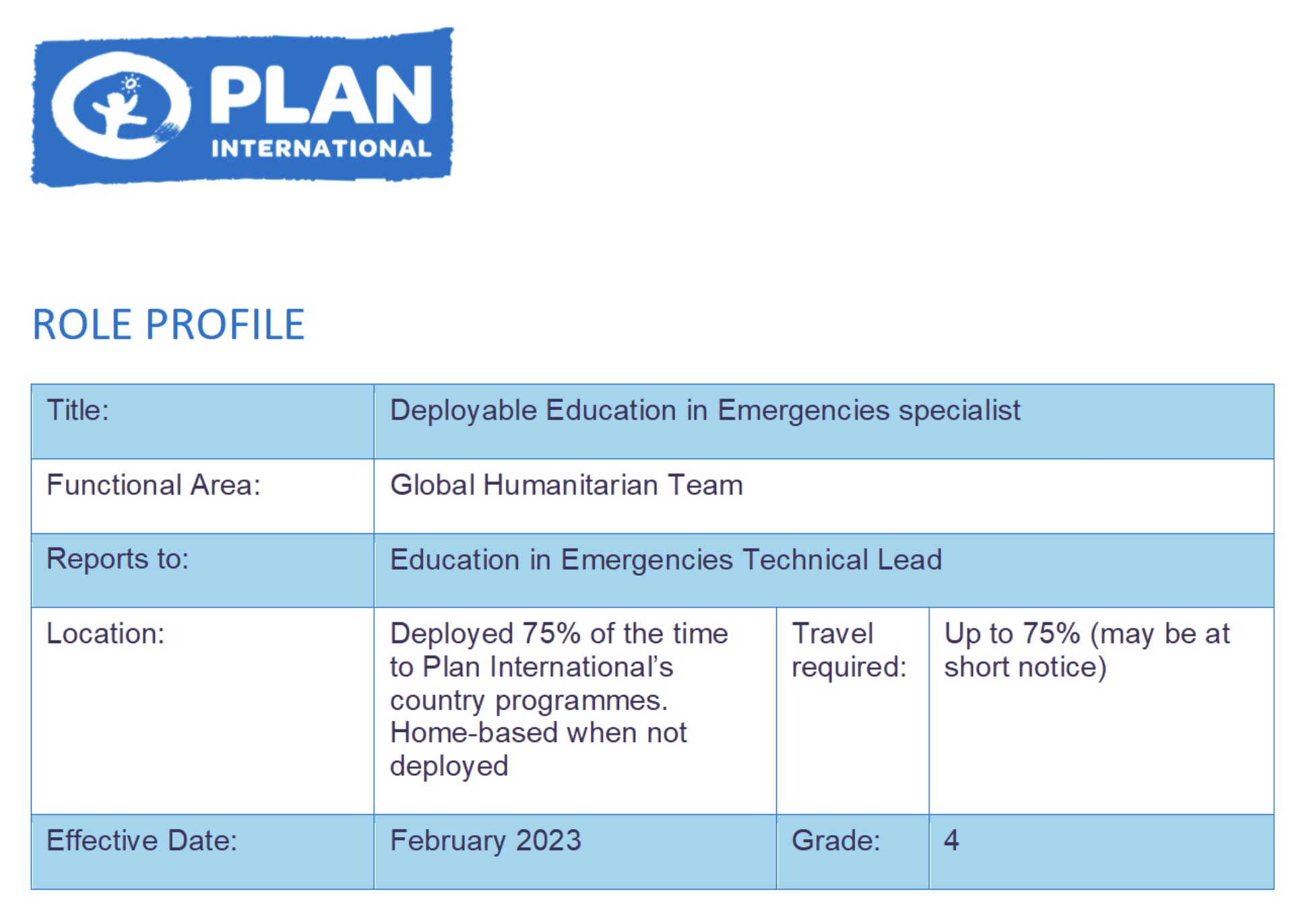

Specialist / Advisor:

Specialists are typically senior positions, sometimes even requiring more than a decade of experience, but without managerial responsibilities. They also rarely have any authority over project budgets. Rather, their role is often strictly advisory.

For example, a CCCM Specialist in Site Planning might be deployed to a mission for several months in order to provide guidance while the CCCM Project Manager in the country constructs a new IDP site. Or, a Cash Advisor might be hired as a consultant by an NGO that is expanding its programming into Cash for the first time and needs expert advice to ensure quality control for its initial projects.

In terms of organisational hierarchy, Specialists or Advisors are wild cards. Although it would make sense for them to report to the Manager in their technical area — for example, a Protection Specialist reporting to the Protection Project Manager — their seniority and advisory capacity means they sometimes report at a higher level to the Coordinator or even directly to the Country Director.

Once someone reaches the level of being a Specialist or Advisor, they often end up working in headquarters or as consultants, deploying around the world for short-term assignments.

Coordinator:

In the humanitarian encyclopedia, “coordination” means identifying gaps in an emergency response and directing NGOs and UN agencies to fill those gaps. That is what the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs does; it’s what Cluster Coordinators do, and it’s what Camp Coordinators do.

Confusingly, it has little to do with the common job title “Coordinator”, which is more a marker of seniority than an indicator of being good at coordinating. Basically, Coordinators manage the Managers. In a classic setting, an Emergency Coordinator with an NGO would supervise the WASH Manager, the Shelter Manager, the NFI/Cash Manager, the Protection Manager, and so on.

Coordinators are senior technical roles, requiring significant expertise in a wide range of humanitarian programming. They are also strategic and forward-looking, planning the projects and anticipating the challenges for next six-to-twelve months. The daily activities of current projects — like organising a cash distribution, digging a borehole, rolling out a vaccination campaign, or checking the quality of shelter materials — are often left entirely to the Project Managers and their teams. As you can imagine, Coordinators’ excursions to the field are rare: typically only to accompany donor or government visits, or to sort out major problems.

Head:

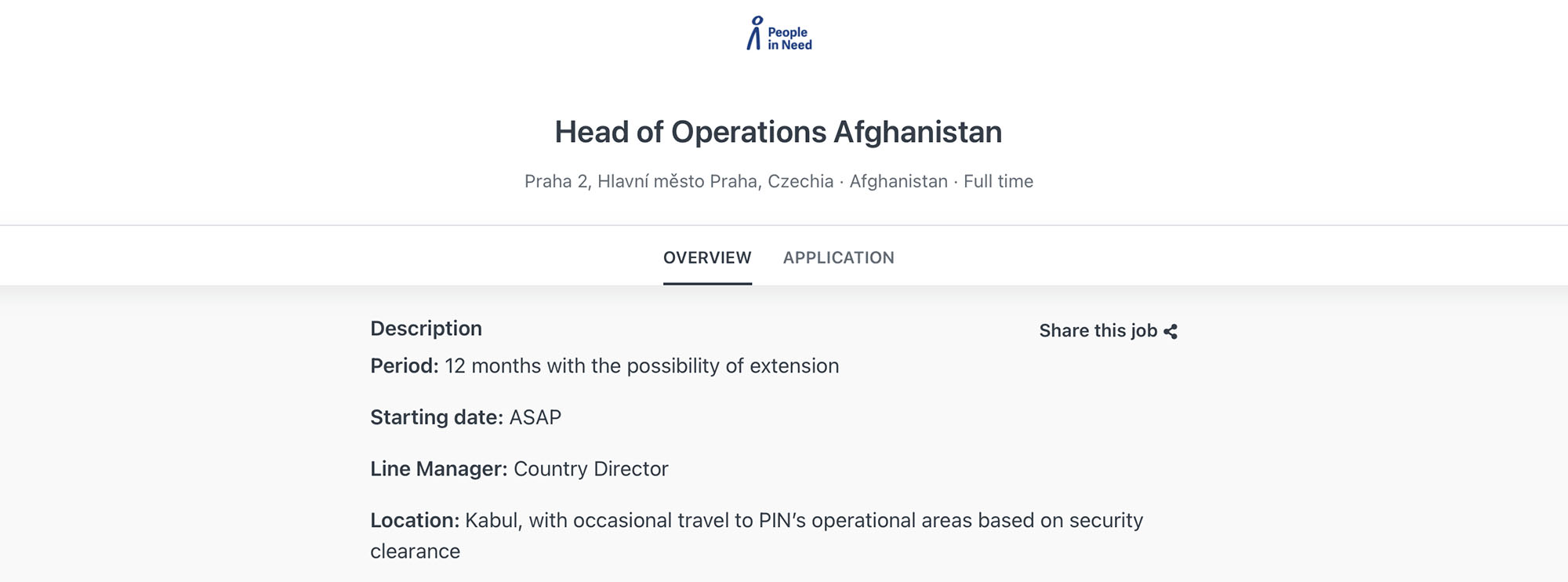

Like a Byzantine double-headed eagle looking to both the eastern and western halves of the empire, there are usually two Heads in a humanitarian country office: a Head of Programmes and a Head of Operations.

Head of Programmes’ territory includes everything related to the humanitarian work of the organisation: the Shelter, Cash, Protection, WASH, and other projects, as well as the monitoring and evaluation of existing projects and fundraising for new projects.

Head of Operations, on the other hand, presides over the administrative side of the organisation: Human Resources, Logistics, and Procurement. Sometimes the aforementioned geographically-organised Area Managers or Heads of Sub-Office also report to the Head of Operations (I know, I know: one Head reporting to another Head; it’s confusing).

Finance and Security teams are usually outside of this dual-head arrangement and report directly to the Country Director.

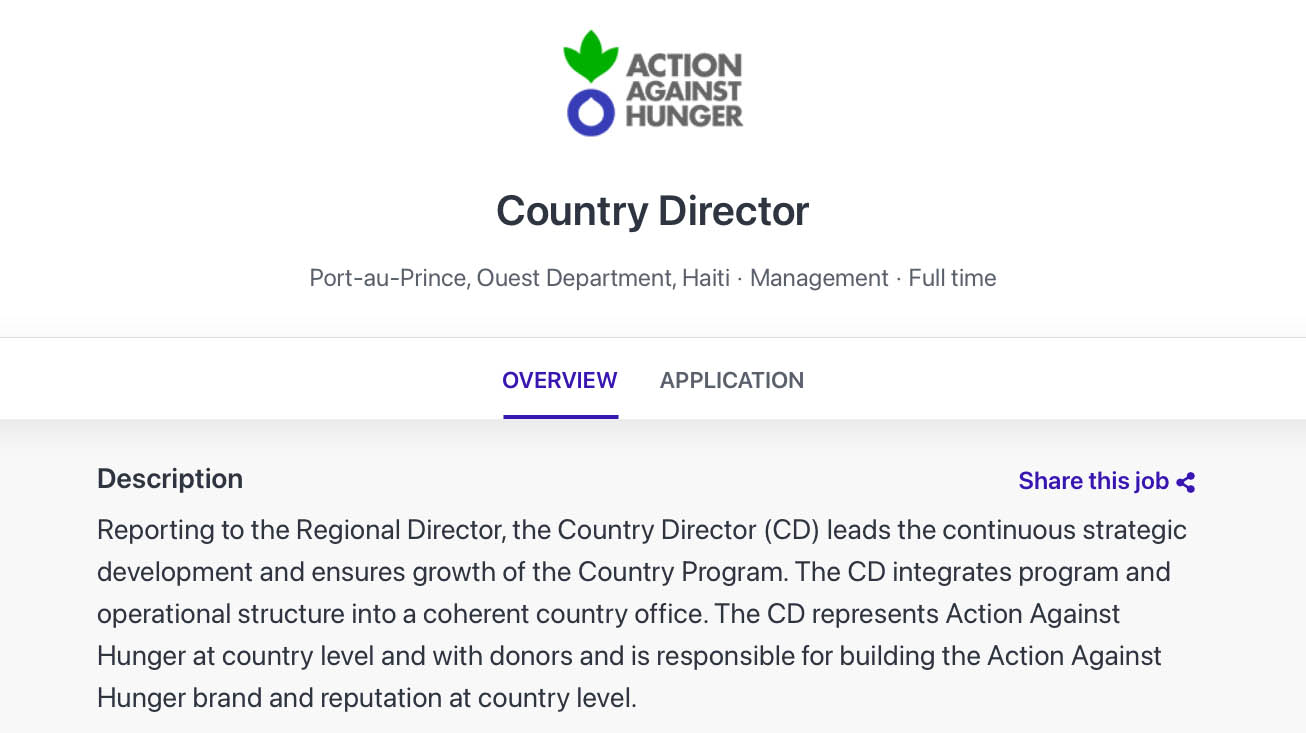

Country Director:

If it has “Country” in the title, it is highest ranking member of the organisation in the country. This position is effectively each aid agency’s viceroy in situ, and they are delegated substantial decision-making authority in the country. They’re the boss. Across different NGOs and UN agencies there are many variations on the title, including:

- Country Director

- Country Manager

- Country Representative

- Chief of Mission

- Head of Mission

- Head of Country Team

Since it will likely be a few years until you, dear aspiring aid worker, attain the rank of County Director, we’re skipping over explaining this position in great detail. Just skim the ACF job summary below if you’re really curious. (Yes, we’ve run low on creative juice.)

The hierarchy of the job titles

But how do all of these positions fit together, and what does the hierarchy look like? Well, thankfully, we can stand on the shoulders of Daniel McCallum, inventor of the modern organisational chart.

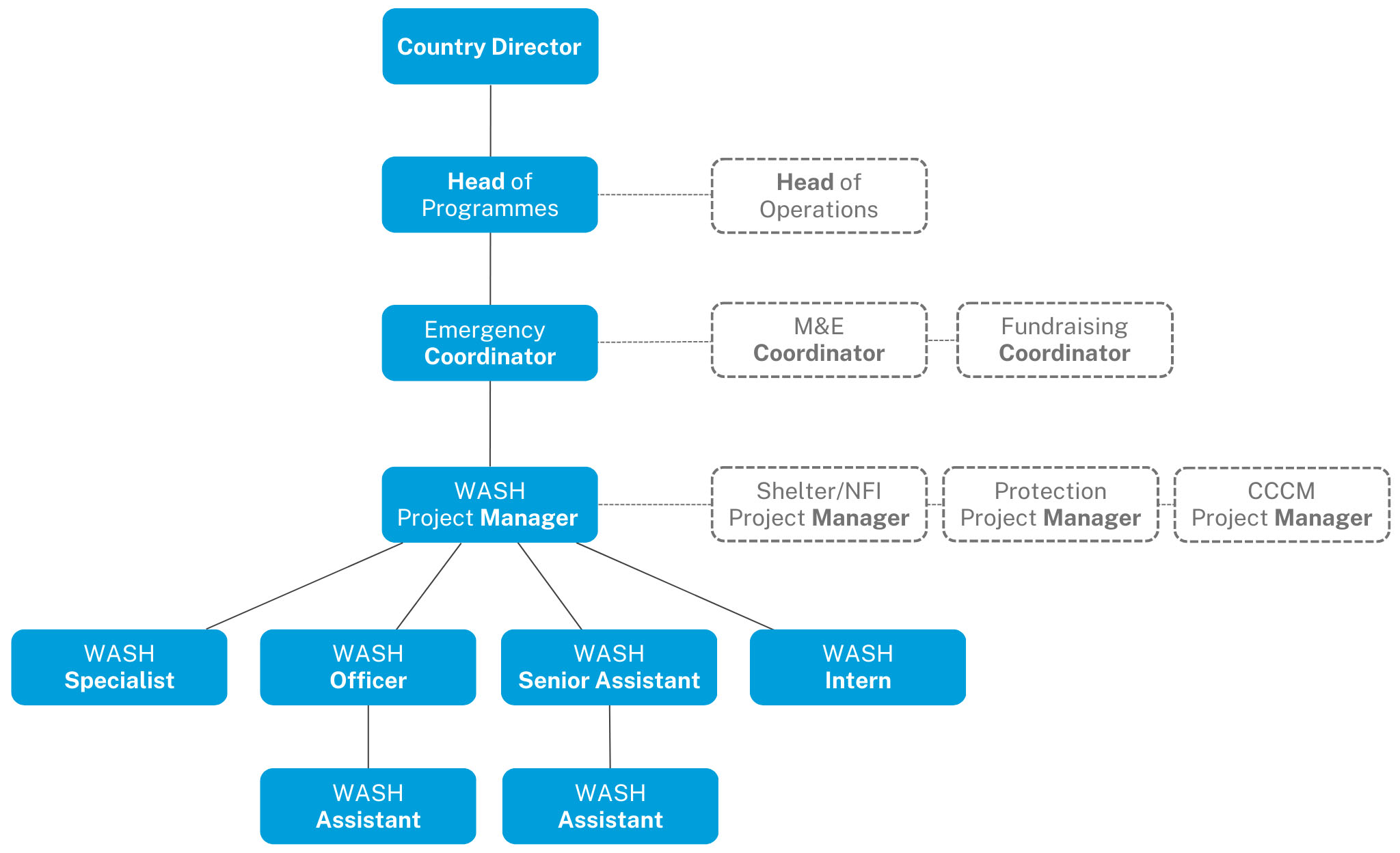

Below is an extremely simplified visualisation of a typical humanitarian NGO organigramme at the country level. Emphasis on extremely simplified. The blue shapes are the positions described in this article, with WASH used as the example for the technical area. The dotted-line shapes hint at the other positions in the organigramme, omitted for the sake of clarity.

It’s important to remember that each organigramme will differ significantly in every organisation. If you’re already a career humanitarian, please don’t write to us to say that your NGO’s org chart is different. We’re well aware that it probably is.

Job titles to target as an entry-level candidate

In our very first article, we cheerfully stated that finding humanitarian vacancies online was a simple three-step process:

- Go to reliefweb.int/jobs

- Filter by 0 – 2 years of experience

- Apply to any and all jobs that interest you

However — and to distill this entire article into a single sentence — if you are genuinely an entry-level candidate with very minimal prior work experience, you should aim for humanitarian jobs with titles like Intern/Volunteer, Assistant (if you are a citizen of the country where the job is posted), or Officer.

April 2023

Related posts

The sheer number of aid organisations can be overwhelming. So we made a list. This is the definitive roll call of every major international humanitarian NGO.

Don’t bother with the United Nations. Aim for NGOs that you’ve never heard of before.

Hiring managers from across the aid industry give their advice on what makes a great CV and cover letter. However, they don’t always agree.

You could skip this article and just go to ReliefWeb. But why skip all the fun?

The veteran Camp Manager explains why the job is among the most challenging in the industry. And why, after nine years, it’s also her favourite.

From medical assistance and food distribution to logistics and finance, your humanitarian career is shaped by your technical specialisation.

Weeklong rest-and-relaxation holidays are a common feature of humanitarian contracts. Is it the best job perk ever or the framework for a lonely lifestyle?

The Syria-based Protection specialist reflects on the power dynamics of aid and the privileged position that humanitarians often have in fragile countries.

Growing up in rural Sweden, the Red Cross delegate never aimed to be an aid worker. Now, at 33, he has built a career working with communities amid crisis and conflict.