Pierre

Budgets and audits may not seem likely pathways to an impactful humanitarian career. But for the seasoned Finance Manager, the job is about people, not numbers.

I remember Pierre’s last day of work in Afghanistan many years ago. At age 25, he had been serving as Head of Finance, overseeing the NGO’s operations across the entire country. It was a demanding job, and the type of back-office role that — let’s be honest — rarely inspires others. But as Pierre left for the airport, the entire office turned out to say goodbye. More than thirty people came to the carpark to give gifts, handshakes, and words of sincere thanks. I can assure you that this was not the standard procedure for departing staff.

That, in a nutshell, is Pierre. His humanitarian career may have focused on finance, compliance, audits, and other terms that most people associate with Deloitte or KPMG rather than humanitarian response. But his career has always been about on making an impact on people. Over the years, he has remained thoughtful, reflective, and earnest — and always ready to lighten the mood with a dry joke and a wry smile.

These are excerpts from our Skype conversation in November 2023. (Yes, we still use Skype.)

When you’re at a party and some asks what you do for a living, what do you say?

Well, it’s different from what I say to airport authorities. I just tell them that I’m an accountant and they always let me go. [laughs] But no, seriously, I tell people that I’m working for NGOs on the financial side.

In my current role in Colombia I have a regional responsibility. I’m the financial focal point for the Norwegian Refugee Council [NRC] in all of Latin America. My job is to give a second view on anything related to finances, like budgeting, proposal writing, reports, audits, and compliance. I can also be mobilised for things like fraud investigations. That’s roughly what I do.

All the things you just listed — finance, audits, accounts — are the things that bored me the most when I was an aid worker. I’m so glad there are people like you who enjoy doing it.

Well, it can a bit dry sometimes, to be honest. [laughs]

How long have you been an aid worker for and where have you worked?

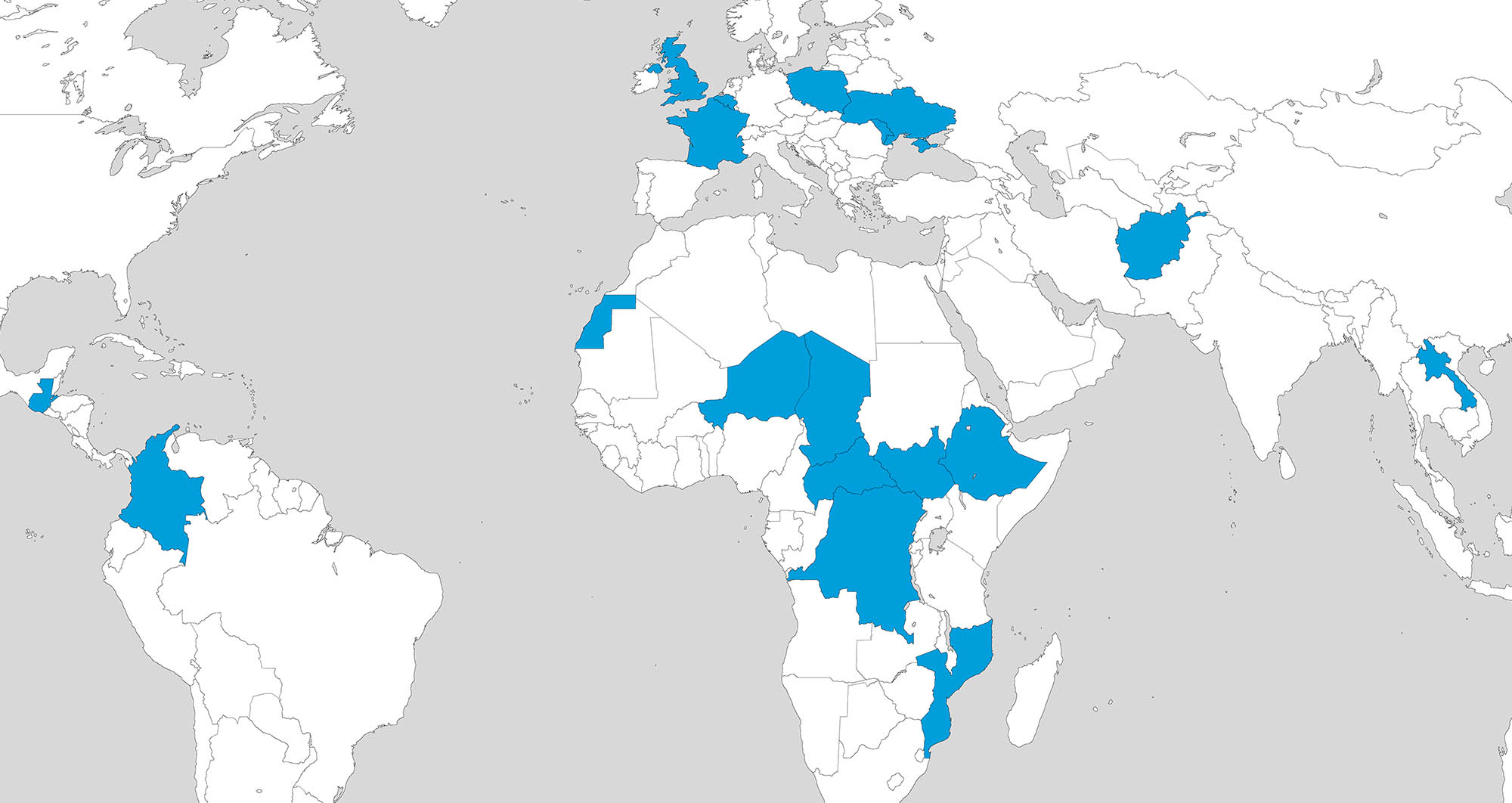

I think it’s around nine years now. Let me try to remember all the countries: Guatemala, Chad, South Sudan, Niger, Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Western Sahara, Central African Republic, the DRC, Laos, Moldova, Poland, Romania, Ukraine, and now Colombia.

France also, no?

Oh yeah, I worked in France of course! And also the UK and Belgium in headquarters roles.

And which NGOs have you worked for? Because you’ve changed organisations a lot in your career.

I started with ACTED, then Save the Children, then I worked for the International Centre for Migration Policy Development, then Oxfam, Lawyers without Borders, Plan International, and now NRC.

Take us back to the beginning. How did your career start?

In university, I had the chance to do a double diploma in France and Spain. That’s why I’m now in Latin America to use the Spanish that I learned all those years ago.

In Spain I studied administrative sciences, and in France it was international cooperation. At the end of my studies I had an exercise to assess a humanitarian project, mainly the programme-related aspects.

I remember thinking, “This is really interesting, but I’m missing the financial side of things.”

Soon after, I found an internship with ACTED in Paris, in their Internal Audits department. So that’s where my career officially started: in an international humanitarian NGO at headquarters. Then I moved to the field in several countries with ACTED, still doing internal audits. Eventually I had the opportunity change my career to the finance side and I have stayed in NGO finance ever since.

You’ve never worked for the United Nations. Was it a conscious decision to only work for NGOs or was it by chance?

I would say it has been both. When you enter the UN system, you can only be a small part of a big machine. You need to be quite senior if you want to manage lots of people and have a significant impact. Of course, the pay is way higher in the UN and there are other benefits.

Actually I had this dilemma recently just before starting with Plan International. I had another opportunity with an international organisation, but the job was not as interesting as opening the new Ukraine mission for Plan.

So, I thought, “Do I want to have a less exciting job that pays more? Or do I take a small sacrifice on the salary and do something that I enjoy more?”

I chose the job satisfaction. That has been case throughout my career.

Do you think you can have more impact working for NGOs?

You can have more impact. You’re more hands-on and you can see the direct results of your own actions. The career progression is faster in NGOs, too.

With a humanitarian career, you have kind of a triangle formed by: one, an interesting job, two, a safe or enjoyable duty station, and three, attractive remuneration. For most of my career, it was nearly always “pick two only”. Now for the first time, in my role with NRC in Bogota, I have the full triangle!

Is that another thing you’ve liked about being on the NGO side of things: the ability to have more responsibility at a younger age and therefore a greater impact?

It is really appealing when you’re starting your career. You can see your career grow every year, or even every six months, within an organisation like ACTED.

Of course, you have to counter-balance that with the potential for burnout. You are often going to work extremely long hours in the field, and not everybody will like that. Among the senior expats in some international NGOs, there is huge turnover because there is too much pressure. The additional responsibilities come with a lot of personal sacrifice.

I would add, with a tiny bit of self-criticism: You also have to always remind yourself that you are there because you are from a privileged background. You are managing people — national staff — with sometimes 20 years of experience and they know better. But just because you come from the West, you will be the one directing them. There is a huge discrepancy in terms of opportunities for expats and national staff.

Why did you choose the operations side of humanitarian work, specifically finance? Let’s be honest, most people who go into humanitarian aid want to be in the field working with communities, not building budgets.

I’ve always enjoyed numbers and finance. I think it’s where I can maximise my impact. You also have to take that into account when planning your career: what added value can you bring to an organisation?

Being on the finance side of things, you are at the centre of everything. You can influence a lot because at the end of the day, it comes down to money. You can write the best theory of change for a new project, but if you don’t have the budget to support that theory of change – poof – it’s just words on paper.

But I always keep in mind that finance is not the core business. You’re always in support. You’re there to help your colleagues achieve things in a better way, to ensure that no money is wasted.

Also, working in finance, you will get to work on nearly all types of humanitarian programming: protection, WASH, shelter, food security, cash, NFIs, camp management, livelihoods, and so on. I think the only one that I’ve never touched is medical projects.

Do you think it’s easier to get a job on the operations side of a humanitarian organisation, because it’s less competitive? For example, I’ve heard it said: “There is always a job in logistics,” because so few people want to do it.

There is some truth to that, but there are also not as many positions for people in this career path. For example, you will only need one Finance Manager per country per organisation. So, true, there is less competition for jobs, but there are fewer jobs.

Is it possible to have an exciting field career while working in a support function, or are you doomed to sit behind a desk forever?

On the contrary, I think that if you want to be a good humanitarian finance manager, then you should be spending a lot of time out of the office and in the field.

Remember, it’s never only numbers. It’s not just about the finances. You must physically check in with your projects to understand the reality and to remember what are the stakes. On the personal level, it’s also incredibly rewarding to work on a budget and then, months later, to see people receiving that assistance. If you never go to the field and see this, you will lose interest.

What is one of the more memorable moments of your career?

I remember one time when I went to Afar, in the Ethiopian desert. We had a big meeting there with local leaders about an education project for girls. The meeting goes on and on, and we have lots of discussions on how to design this very big project.

At some point, I noticed that only men were speaking. I had the microphone in my hand, so I just handed it to one of the women, who happened to be from the Ministry of Education and asked her, “Do you agree?”

And she said, “Well, I agree, but…” [laughs] …But no.

She basically said, “If you do what you’re proposing now, you will not achieve your impact. That’s not what girls really need in order to go to school.” She slashed everything that the men had just proposed.

What was the reaction from the men?

It was… mixed. However, thankfully my NGO had also brought to this meeting several experts and specialists — who were also women — who immediately validated the woman’s points and didn’t allow space for the men to go back to the original proposition. There were a few minutes of people trying to push back and argue, “We’re not really going to re-do the entire project design at this stage, are we?”

Because of my position as the Finance Manager, I was able to smile and say, “Yes, actually we still have time!” [laughs]

That was really nice.

Let’s talk about languages. You’re French, but you’ve spent a lot of your career working in both English and French, and now in Spanish. Has knowing multiple languages helped you in your career?

Good question. I think languages are quite important, especially English. If you don’t speak English, it will be a dead end for your career. I started my career not feeling super confident with my English. In fact, I spoke Spanish much better than English at that time. But since then I’ve basically spent my entire career speaking in English and writing in English.

To answer your question, there is a segregation of the languages you need to speak in order to be deployed to different countries as an aid worker. The main languages of the industry are English, French, and Spanish.

For instance, you cannot hope to get a position in Latin America if you don’t speak Spanish. That’s because the national staff will not speak English. If you speak French and a little English, most likely you will start your career in a French-speaking part of Africa because of the same issue: national staff will only speak in French at the office.

English will be much more prominent among national staff in east Africa, the Middle East, and parts of Asia. So you could definitely get a position with only English in these parts of the world. For expatriate staff in the Middle East, speaking Arabic is not a “must”; it’s more like a cool addition to your CV. If you don’t know Arabic, it’s unlikely to be a barrier for you, as most of the time the national staff will be really skilled in English.

If you are a national staff who wants to become expatriate staff, not having a good level of English can be a barrier for making the jump from national to expat staff. Again, it’s all a play of neocolonialism because most of the countries where we are working are speaking the past coloniser’s language.

What do you do on a daily basis as a humanitarian finance manager?

When you work in finance, you are exposed to more deadlines than any other job in the aid sector. Because, while each project may have its own deadline, all of the projects’ deadlines are your deadlines!

You are also often the last piece of a new project proposal. If your organisation has 48 hours to do a new proposal, you, as the Finance Manager, will have only four hours to finalise the budget. You need to be able to work under time pressure.

By default, working in a humanitarian support function, you will only see the problems. Nobody is ever going to say to you as the Finance Manager, “Oh, by the way, great work!” No, it’s always just, “We have this problem. We have that problem.” Sometimes it’s 30 problems in a day and you have to solve them all.

You will also spend a lot of time coordinating with people. In a Country Finance Manager position, you typically liaise with all of the field bases across the country, understanding their context, and doing a lot of problem solving. That’s what I enjoy about the job: being a bridge between colleagues who would not normally speak together.

Because I have a more generalist background than just pure finance, I can also understand the programme issues. I can translate numbers into human, and human into numbers.

Oh, I also use a fair bit of accounting skills on a daily basis, but mostly common sense. You will need to advocate for common sense.

It sounds like a lot of pressure from all sides.

Yes, and it’s a lot of emails, too! [laughs]

What do you wish someone had told you about humanitarian work before you started?

I’m a bit of an idealistic person. You need to know that no aid organisation is perfect. Yes, some organisations are better than others, but they are usually harder to get into. But regardless, you will never find a perfect humanitarian organisation. Therefore, you always have to weigh what are you getting from an NGO in terms of satisfaction — and that can be as silly as just the salary — versus how much you are giving.

On another note, something that I’m happy that I realised quite quickly is this: I’ve seen people dedicating their whole lives to humanitarian work, and then they suddenly wake up at a certain age — maybe 40 or 45 — and they realise that, yes, they have friends all over the world, that’s nice. But they don’t really have any roots. They haven’t built anything apart from their career. They don’t have a home; they don’t have a partner.

So my advice is: don’t forget to nurture your life outside of your humanitarian career. Because you can be dragged into work, work, work, and you’ll wake up one day and you won’t have a life.

I totally agree. On the second point, I think most people have the option to exit aid work between age 30 or 35. The ones who don’t, then they do sometimes wake up at 45 or 50 and regret it.

And they’re cynical. You get more cynical the longer you stay.

How do you avoid becoming cynical in your work?

First, I enjoy my fair share of dark humour. But honestly it’s always a balance between knowing that you’re acting on the agenda of someone else — specifically donor governments — but also realising that if nobody was doing it, the situation would be worse. It’s about acknowledging simultaneously that you are not saving the world, but that you are still doing an important job.

Last question: Where do you see yourself in five years, at age 38?

It’s way too far away for me to imagine. There are personal life goals that I want to achieve within the next three years: getting officially married and having my first child. Depending on those, my career may change a bit.

Also, I think NRC is one the best humanitarian NGO — or at least this is what we’ve all been told. So I wanted to check them out and see if I can grow in the organisation. But I think it will be the last NGO that I work for.

Also, I don’t have job security. That’s important for people to know. When you have an expat contract, even with an amazing organisation like NRC, it’s only a one-year contract with six-month probation.

Five years is really far away. I will either be still at NRC, doing finance for the region or something like that, or maybe switching to other support-related functions, or HR. Or maybe I’ll move to the private sector.

November 2023

RELATED POSTS

The veteran Camp Manager explains why the job is among the most challenging in the industry. And why, after nine years, it’s also her favourite.

The Syria-based Protection specialist reflects on the power dynamics of aid and the privileged position that humanitarians often have in fragile countries.

Growing up in rural Sweden, the Red Cross delegate never aimed to be an aid worker. Now, at 33, he has built a career working with communities amid crisis and conflict.

Take a peek inside aid worker accommodation, from apartments and guesthouses to containers and, yes, tents.

An unlucky number of true anecdotes, success stories, and lucky breaks.

Don’t bother with the United Nations. Aim for NGOs that you’ve never heard of before.

Hiring managers from across the aid industry give their advice on what makes a great CV and cover letter. However, they don’t always agree.

You could skip this article and just go to ReliefWeb. But why skip all the fun?