Meti

The second generation humanitarian recalls making the leap from NGO local hire to United Nations international staff, and explains why motherhood won’t mean the end of her career in the field.

At a certain age, many humanitarians feel torn between building either a successful career or a family. But for Meti – daughter to one humanitarian and wife to another – family life and aid work have always intermingled, albeit, she admits, with extra effort required.

Meti has spent most of her career in some of east Africa’s remotest locations, from refugee camps in Ethiopia to isolated communities in South Sudan. After eight years in the field, witnessing many hardships, she maintains an optimism and sincerity rarely found in veteran aid workers. Her career is still, at its core, about helping people.

These are excerpts from our phone conversation in May 2022.

Do you have a most memorable moment from your career?

I remember one time when I was working in the WASH (Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene) sector, and we were trying to drill a borehole to bring water to a local community. We tried and failed multiple times to secure the borehole, but finally after several days we struck water. The relief and joy were incredible. Seeing the people – women and children especially – dancing around the fresh water coming out of that borehole, it was one of those times that I just felt like, “This is awesome”.

I remember another moment that actually made me cry with joy. In rural South Sudan when girls get their menstruation, they skip school for about a week or more – every single month. Imagine! And so I was working on a menstrual hygiene project, and our goal was to improve young girls’ access to menstruation kits.

We were in a very remote area in Upper Nile State called Mayom. We taught women and girls how to make menstrual pads by sewing simple layers of cotton cloth together. It was a very long and highly monitored project. It wasn’t like we just taught them how to sew and then we left. No, we followed up closely to see if the girls were making use of the pads and, most importantly, if they were going to school.

At the end of the project, we did interviews with them and the feedback that we got was amazing. It sounds very simple, but the end achievement was incredible. As a woman, I was really touched seeing those girls so happy.

When did you decide to become an aid worker?

My dad was a humanitarian, and so as a child I was always fascinated about what he did. When he would come home from work, he would tell us stories from the field. That made me think, “I want to be like him. I want to be a humanitarian. I want to help people.” So I was basically following my dad’s footsteps!

When I grew up and started working in the humanitarian sector myself, my relationship with my dad became even stronger. Of course, he was very protective at the beginning because he knows what dangers we face in the field, but equally he was so happy to see me succeed. We’ve become very close friends talking about things that happen in our work.

What’s the story of your career in a nutshell?

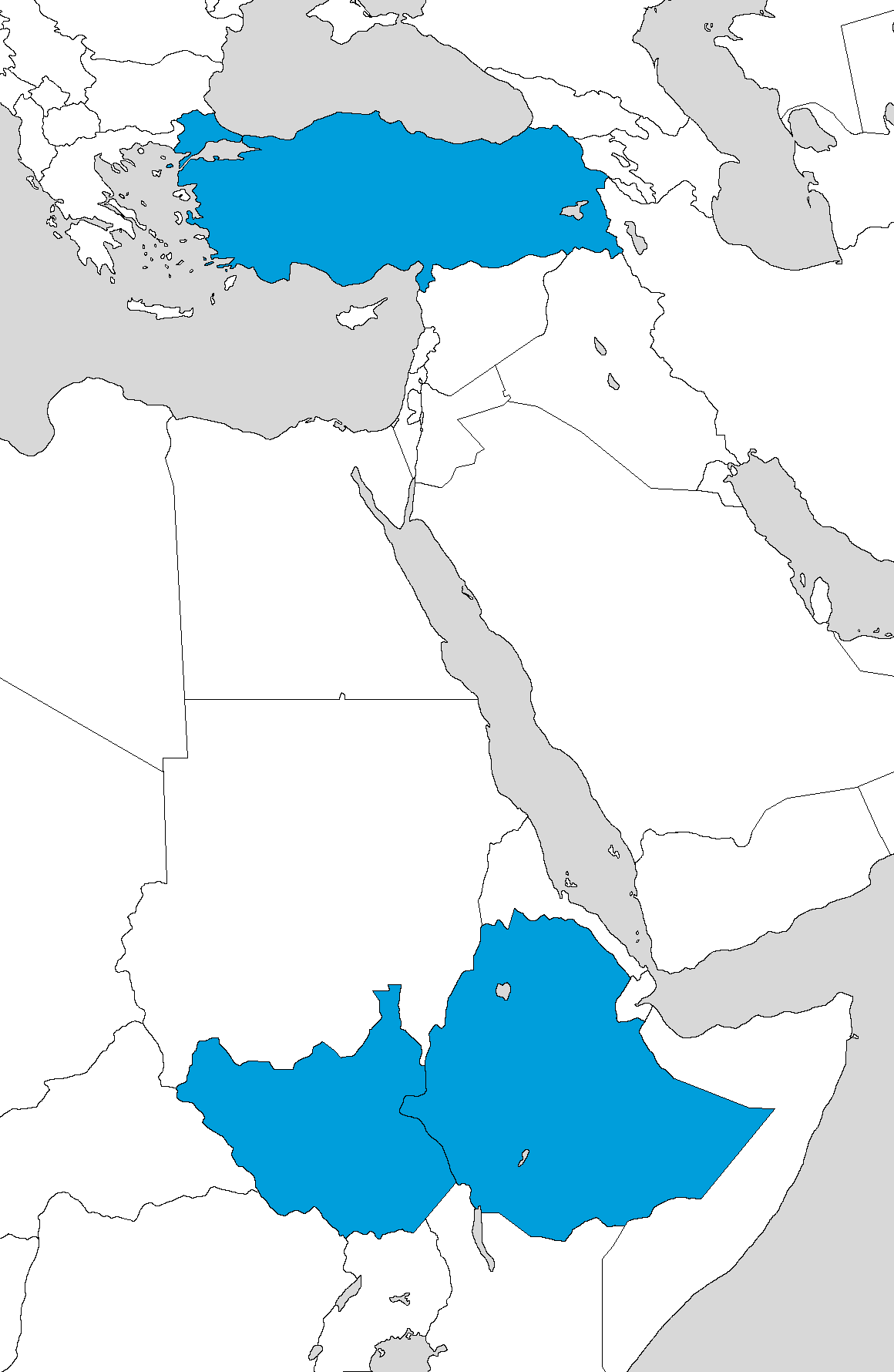

I started in Ethiopia about eight years ago. As you know, the South Sudanese civil war started just after their independence in 2011, and so in early 2012 there was a large influx of refugees coming into the bordering countries. One of the countries was Ethiopia, which received millions of refugees. So I started from there in 2014.

My first job was with Action Contre le Faim (ACF) doing WASH and hygiene promotion. Then I joined Norwegian Church Aid (NCA), and after that I got an opportunity with Oxfam during the cholera outbreak in Ethiopia. All three of these jobs were in the WASH and Health sectors, all within Ethiopia, and mostly in the refugee camps in Gambella. Other people may jump from country to country, but I jumped from organisation to organisation [laughs]!

After two years of this work in Ethiopia, I was hired by IOM, the United Nations Migration Agency, in South Sudan. This was my first international post and my first with a UN agency. For about three-and-a-half years I was posted in quite remote places working in the WASH sector and also supporting the Health sector during the Ebola prevention, preparedness, and response project.

Finally, over a year ago I was deployed to Turkey with IOM to work on the Syria response, where I am now. I’m the Capacity Development Officer here and I’m responsible for strengthening the capacity of our implementing partners and their staff. My role is more multi-sectoral now.

Was it easy to get your first job in the field?

When the time came, I applied to lots of humanitarian positions but I was not very successful initially. At one point I even remember thinking to myself that this career was not going to happen for me. Even though I had built up a network of humanitarians in my life – my dad and his friends who worked for NGOs – it was still very difficult, honestly.

In the end, it was my university education and practical skills that helped me break through. My bachelor’s degree is in Public Health and my master’s degree is in International Cooperation and Humanitarian Aid. My very first job was working in hospitals and supporting the outreach aspect of public health, for example encouraging people to go get treatment and these sorts of things.

When the South Sudanese refugee crisis happened, so many NGOs – local and international NGOs in Ethiopia – opened vacancies for entry-level positions. I applied for this job at ACF in Gambella doing community engagement on public health issues, and, luckily, that was exactly the type of work that I was already doing in the hospitals. That’s how I got my first job!

You mentioned a unique characteristic of the aid sector: When crises happen in the world, they are often the starting points for many people’s humanitarian careers. I think of the Haiti earthquake in 2010 or the refugee crisis in Greece in 2015. Now Ukraine is the global crisis. Many old-timers in the aid sector started their careers in the Balkans in the 1990s. The headline crises are where the bulk of global aid funding goes, and with funding comes job openings.

Yes, I agree. Unfortunately, career opportunities in our sector come where bad things are happening in the world. Specifically, I think young people should look at events that are happening close to their own country. Usually during a crisis there are refugee movements into neighbouring countries, which creates a need for aid workers with specific regional language skills.

For example, in the humanitarian responses in the Middle East you will typically find many international staff who are Arabic speakers who started their careers in countries next to those experiencing conflict. In my case, my native languages are Amharic and Oromifa. I was able to use both languages extensively during my work as a national staff in different parts of Ethiopia.

There is another advantage to starting your career in a neighbouring country: you don’t have to be far from home. That’s something that helped me. I started my career within Ethiopia, so it didn’t feel like I was going somewhere completely different, and even when I moved to South Sudan it was still not far.

You started your career as a locally-hired national staff and then became an international staff. Why do so many humanitarians aim to make this jump to international work?

Starting as a national staff is a great entry point to the aid sector, but there are huge benefits that come with being an international staff, like better salary and more frequent breaks in your work.

When I was in Gambella as a national staff, I was given a break every 12 weeks, while my international colleagues got a break every six weeks. This was despite the fact that I’m not from that region of Ethiopia and I was also far from my family and was equally affected by the hardships and conditions of the place.

In all humanitarian responses, the pressure on national staff is heavy. International staff rely on our knowledge to understand the context, the culture, and the language. So yes, that is something that is worth debating: Why do national staff receive lower salaries and fewer privileges despite a heavy burden?

But when you’re a national staff, what’s most important, I think, is to have a clear objective. For me, my goal was to gain experience in hardship duty stations so that I could learn and build my skills and one day transition to being international staff.

What’s the hardest part about having a career as a humanitarian?

In the beginning, I struggled with comprehending how unfair this world is. People are suffering so much: for example, seeing children injured from war or seeing children separated from their parents. All those things make you feel really sad. I was depressed for my first few months in the field.

Then you get kind of used to it and you focus on how to help, rather than sitting around feeling sad. Eventually you come to the realisation that you can’t change the world, but you can help people who are affected by different crises in small ways.

You have a husband who is also a humanitarian, and you are both expecting a baby very soon! How do you make family life work as a humanitarian couple?

My partner and I had to maintain a long-distance relationship for years because of our careers. We met when we were both working in South Sudan and so we had the opportunity to build the relationship together for the first few years. Then he moved to Ethiopia while I was still in South Sudan. Then he went to Bangladesh and I went to Turkey. Then he went to Nigeria!

There have been many distances over the years, but we made sure that we had strong communication and put in the effort to make the relationship work. For example, we meet on every R&R: either he comes here to Gaziantep or we go somewhere else together.

Now, as you said, we are about to have a baby in a few weeks. We will be together for about four months after the birth before he must go back to Nigeria to finish his first-year mission with the ICRC. After my six months of maternity leave is finished, I will go back to work and he will become a stay-at-home dad.

Has it been a challenge to grow a meaningful relationship and start a family as an aid worker?

Definitely. Meeting your future partner is not as easy when you’re in the field. If you live in a normal city, for example, you have lots of opportunities to meet people, right? But in a remote field post, you might only have a limited number of people who you interact with every day. You don’t have many chances to meet new people or to build meaningful relationships.

But that doesn’t mean it never happens! I am just one example, and I have a couple people I know who were able to build families after their humanitarian career. I can’t say it’s based on luck, because it takes determination to meet your life partner while working in the field.

Do you see your humanitarian career changing with the arrival of your baby?

My agreement with my partner is to continue being humanitarians for the next few years, but trying to find places where all three of us can be together in family duty stations. I may not be able to travel to remote areas like I used to, but it doesn’t mean that I will stop working in this sector.

What do you love about being an aid worker?

You know, a career in the humanitarian sector is quite challenging. The situations that you face are not usually happy situations. There are days when I get frustrated because of the living conditions or because of seeing so much suffering. All of that affects you mentally.

But at the end of the day, the effort that you make to support people, that is the part that I like the most about it. Even though it’s very little support that you are providing, it’s still very satisfying. Even though you don’t really do much for them, you do help. Those are the simple things that I really enjoy about being a humanitarian.

June 2022

RELATED POSTS

The veteran Camp Manager explains why the job is among the most challenging in the industry. And why, after nine years, it’s also her favourite.

The Syria-based Protection specialist reflects on the power dynamics of aid and the privileged position that humanitarians often have in fragile countries.

Growing up in rural Sweden, the Red Cross delegate never aimed to be an aid worker. Now, at 33, he has built a career working with communities amid crisis and conflict.

Take a peek inside aid worker accommodation, from apartments and guesthouses to containers and, yes, tents.

An unlucky number of true anecdotes, success stories, and lucky breaks.

Don’t bother with the United Nations. Aim for NGOs that you’ve never heard of before.

Hiring managers from across the aid industry give their advice on what makes a great CV and cover letter. However, they don’t always agree.

You could skip this article and just go to ReliefWeb. But why skip all the fun?